This article, which is also available in Spanish, was originally published as a chapter in Donna Goodman’s book, Women Fight Back: The Centuries-Long Struggle for Liberation.

Introduction

The decade of the 1960s saw rebellions and uprisings that lasted until the mid-1970s and resulted in the overthrow of formal segregation, the rise of a formidable antiwar movement, the lasting impact of the women’s liberation movement and the end of many stultifying conservative cultural conventions. The decades of right-wing and neoliberal reaction, that began in the latter part of the 1970s, reversed many but certainly not all of these progressive advances.

Black students from A&T State University in Greensboro, North Carolina kicked off the Sixties with a sit-in at Woolworths on February 1, 1960, which galvanized the nation. The protests spread to Chattanooga, Nashville and other cities. The pace picked up the next year with the first Freedom Rides to protest segregation in Southern interstate transportation started by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The Black and white nonviolent riders were confronted with horrific ferocity and racist hatred at virtually every stop.

Black movements led by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, the Black Panthers, Black working-class union militants and others struggled for freedom and equality throughout the decade, registering major gains in nearly every arena.

As the civil rights and Black freedom struggle continued, one after another aggrieved or radical constituency raised its own oppositional banners to change the status quo in the U.S.: Vietnam war opposition; the student movement and the New Left; the broad counterculture that swept away many stultifying cultural conventions; socialist and communist groups, which all got stronger, including the relatively new Maoist movement; the LGBTQ movement; rank-and-file labor militancy; the Chicano, Puerto Rican, Native, and Asian movements; and of course the rambunctious movement for women’s equality that sought the overthrow of male domination. All of these trends grew amid mass street confrontations, direct actions and a broader spirit of resistance, intersecting with one another from the mid-’60s and remaining an extremely powerful force for the next decade.

Women’s activists Bella Abzug and Dagmar Wilson founded Women Strike for Peace in 1961, in opposition to nuclear proliferation. The group’s first major action on November 1 that year consisted of protests against nuclear weapons in 60 cities by some 50,000 primarily middle-class women. This action and other marches, pickets and sit-ins took place to pressure the United States and Soviet Union to sign the nuclear non-proliferation treaty. During the Vietnam War they initiated anti-draft counseling programs.

The mass movements reinforced each other. Some activists moved from one issue to another, and those who were once on the sidelines joined in. A number of leading women gained experience in the early years of the civil rights struggle and brought that knowledge to the women’s uprising. The existence of several movements at once enhanced all of them, and each tended to support the other. In a way, while different groups and coalitions focused on different issues, in human terms the movements were all interwoven and participants considered themselves part of “The Movement.” All opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam, making that movement the most powerful peace undertaking in U.S. history. Women constituted at least half the many millions who opposed the Vietnam War.

By the time this extraordinary era dissipated in the mid-’70s—around the time the Vietnamese people were finally victorious in the decades of long war against Japanese, then French, then American imperialism—all these movements had created a unique radical environment in America that brought about a number of important political and social advances.

The women’s movement

The publication of Betty Friedan’s bestselling 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, helped spur the Second Wave by illuminating women’s largely concealed dissatisfaction with the drudgery and isolation of full time housework, child care, shopping, etc., in largely male dominant households where a woman was an unpaid housewife. Although the book has been criticized because of its concentration on the white middle class, it played a major role in spreading feminist consciousness and opening the eyes of millions of housewives to a virtually unidentified frustration, the “Problem That Has No Name.” Friedan wrote:

Each suburban wife struggles with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all? [1]’

Writing in the Huffington Post 50 years after its publication, Professor Peter Dreier declared that the book “forever change[d] Americans’ attitudes about women’s role in society.”

In common with many leftists who came through the hysterical anticommunism of the 1950s, Freidan tended to conceal her left-wing ideological influences. She was a former labor journalist for one of the best left-wing unions—the United Electrical Workers (UE)—an organization that was ejected from the CIO in the late 1940s because of government and right-wing union opposition to leftist and “red” unions and union members. She denied ever being a member of the Communist Party though it is clear she sympathized with strong left-wing goals.

It is important to note that most working women in those years wanted more time at home with their children and saw the lives of housewives as privileged. Working-class women faced discrimination in the workplace and suffered from the absence of family benefits that would have made it possible to hold down a full-time job without causing great hardship to their families. In addition, hiring decisions were completely segregated by gender and race, down to the kinds of help-wanted ads that ran in the newspapers: “male help wanted” or “female help wanted.” Jobs allotted to women offered lower wages and far fewer opportunities for advancement.

Once hired, women not only had to contend with discriminatory wages but also with the lack of maternity leave, child care and other family services that were becoming routine in the social democratic societies of Europe. Child care, which had been provided by the state for women workers in the defense industry, was taken away after the war. The loss of this essential benefit was one factor that pushed post-war women workers out of the labor force and into the home. Most of these social services continue to be withheld by the U.S. government—which refuses to raise taxes on the rich to pay for such programs, or cut into the gigantic military budget.

Black women, who were concentrated in agricultural and domestic occupations, suffered the additional discrimination and resulting hardship of having been excluded from Social Security. (Their exclusion had been one of the conditions demanded by Southern lawmakers in exchange for voting for New Deal legislation.) Many of the exclusions were ended in the 1950s.

Not all women of the era went along with the movement. Many preferred the role of family homemaker. It was traditional, could have its rewards and was in tune with the dominant ideology passed down through the state, the Church and the mass media. For financial reasons far fewer women today are in the position to choose whether or not to work—and far fewer prefer to stay at home, thanks to the cultural shifts and breakthroughs into the labor force that can be traced to the gains of the Second Wave period.

The accomplishments of the Second Wave were significant and far-reaching. The changes that benefited women reached deeply into society, and were brought about by a mass, independent feminist movement, which occurred both inside and outside the electoral system and independently of the major political parties. The movement’s primary tactics were street demonstrations, direct actions and small-group consciousness-raising, as well as grassroots community organizing, and interventions against the mass media, popular culture and the courts. Feminist ideas flowed into the main-stream, as women saw gains in law and public policy, private life and popular culture.

The Second Wave of feminism was a truly mass movement that included women of all backgrounds and oppressed communities, as well as political backgrounds, from liberal to communist. The large white middle-class segment had the widest reach into the mass media and the general public, and continues to receive much more visibility in the historical presentations of the era in films and academic works. Unfortunately, this has left a somewhat distorted picture in the minds of many of today’s activists, who are unaware that there was such a large left-wing and revolutionary sector.

This is a glance at the activity and goals of some of the constituencies that were active in the 1960s-70s, and that had a continuing influence in the following decades.

Liberal feminism

Liberal feminism emerged from the historical women’s rights movement. It consisted largely of white middle-class women including a professional sector that made demands on federal and state institutions to end the discrimination that women experienced in the workforce. These women also tended to be married mothers, and their demands reflected the experiences and dissatisfaction of many housewives [2].

The goal of this current was to open up the existing political and economic system to women and to achieve political, legal and social equality with men. Activists’ political lives centered on political parties, unions and other institutions where they engaged in coalition building, electoral politics and union organizing, while working with male allies. They did not challenge the capitalist system and sought reform from within.

As this current grew, it developed closer ties with the Democratic Party and stressed lobbying and electoral politics as primary political strategies. The Democratic Party, in turn, made room to absorb these elements into its party machinery as a new loyal and influential constituency. Liberal feminists led and continue to lead campaigns for important legislative and policy changes.

The federal government began to pay new attention to women’s equality issues in the early 1960s, thanks to the pressure brought by women activists and the growing visibility and successes of the civil rights movement. The U.S. Women’s Bureau urged President John F. Kennedy to create the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. The President appointed the commission in 1961 and selected Eleanor Roosevelt to chair it. Based on the Commission’s recommendations, President Kennedy in 1962 ordered federal government agencies to stop discriminating against women employees [3].

The Commission’s first report, called “American Women” and issued in 1963, contained some progressive recommendations that have since been enacted, such as more equitable employment practices, legal treatment and property rights for women. But half a century later, many of the core reforms that the Commission recommended still have not been realized, including pay equity across occupations and expanded services for working women, such as paid maternity leave, home services for working mothers and child care.

The report also addressed the oppression caused by poverty and racism as well as gender inequity, noting that the racial discrimination that deprived Black men of opportunities for employment created additional economic responsibilities for women: “Such women are twice as likely as other women to have to seek employment while they have preschool children at home; they are just beginning to gain entrance to the expanding fields of clerical and commercial employment; except for the few who can qualify as teachers or other professionals, they are forced into low-paid service occupations.” The report pointed out the similar situations and discrimination faced by Native Americans and Latinas.

National Organization for Women

The most important popular manifestation of liberal feminism was and is the National Organization for Women (NOW), which became the largest mass-membership feminist organization in the country with a reported half-million members today [4]. It was founded in 1966 by feminist activists, with Betty Friedan as president, in part in response to the fact that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination in employment, was not being consistently enforced. According to its statement of purpose the organization intended “to take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partner-ship with men.” The statement criticized the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) for not taking seriously enough the discrimination faced by women and the double discrimination suffered by Black women.

The organization took on the legal issues of wage discrimination; the dearth of women in the professions, government and higher education. It also stressed the need for policy to catch up to changing realities in the family: women were chafing against their unequal position in marriage. In addition, they were outliving their child-raising years, thus removing a major rationale for limiting them to the realm of the home.

In its early years, the NOW leadership was hostile to lesbian activists and issues, and had a weak position on abortion rights. Friedan herself made statements against the “lavender menace.” Internal struggles led the group to become more inclusive over time, so that by 1971, amid the explosion of the lesbian and gay liberation movement and the growth of radical feminism, it embraced lesbian members and their cause, and gave strong support to abortion rights.

NOW’s bill of rights, passed in 1967, called for enforcement of laws banning sex discrimination; maternity leave rights in employment and in social security benefits; tax deductions for home and child care expenses for working parents; child care centers; equal and integrated education; equal opportunities for job training and housing, and family allowances for women in poverty. That year also saw NOW’s endorsement of legalized abortion.

Although the majority of its members were white, NOW was racially integrated from the start, and some of its charter members were veterans of the civil rights movement who saw the need to address discrimination on the basis of race and gender at the same time. Pauli Murray, civil rights worker, lawyer, feminist activist and the first Black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest, wrote:

“The Negro woman can no longer postpone or sub-ordinate the fight against discrimination because of sex in the civil rights struggle but must carry on both fights simultaneously. She must insist upon a partnership role in the integration movement.” [5]

NOW had close ties to leading labor unions and for its first year its office was in the United Auto Workers (UAW) Solidarity House in Detroit. The UAW also contributed financial support to help it get started. Among NOW’s founding members were members of UAW, CWA, and the United Packing House Workers—including Addie Wyatt, a founder of the Coalition for Labor Union Women (CLUW).

NOW engaged in street actions, lawsuits, boycotts, lobbying and electoral campaigns. Petition drives against the EEOC, supported by sit-ins at the agency’s field offices, helped bring about an end to sex-segregated job ads.

The organization also campaigned hard in 1972 for the presidential run of Shirley Chisholm, a NOW member and the first African American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Chisholm wrote in 1970: “The harshest discrimination that I have encountered in the political arena is anti-feminism, both from males and brain-washed, Uncle Tom females. When I first announced that I was running for the United States Congress, both males and females advised me, as they had when I ran for the NY State Legislature, to go back to teaching—a woman’s vocation—and leave the politics to the men.” [6]

Other liberal feminist projects

Ms. Magazine was an important manifestation of the rise and impact of liberal feminism. The publication was founded by Gloria Steinem and others in 1972 with the goal of promoting feminism without having to compromise to the management of anti-woman advertisers and editors.

Steinem was a journalist and feminist activist who had first gained recognition by working undercover in a Playboy club and writing about the unfair conditions endured by Playboy bunnies. She was a co-founder of the Women’s Action Alliance, the Coalition of Labor Union Women and Choice USA, among other organizations. The magazine was criticized by radical feminists for working within the traditional publishing world, featuring mostly white, straight middle-class professional women, and for promoting Steinem as a spokes-person of the movement. Nonetheless, Ms. broke several feminist ideas into the mainstream, openly discussing, for instance, women’s sexuality and publishing the names and stories of women who had abortions—in a magazine that was on newsstands across the country.

In 1967, Steinem had admitted to working with the CIA as a student activist in the 1950s and early 1960s, but denied the allegations of radical feminists that she continued her collaboration. In early 2016, Steinem made headlines for quite an anti-feminist comment in a television interview that young women were supporting Bernie Sanders because “that’s where the boys are.” She soon apologized and said she had misspoken.

Ms. Magazine is now published quarterly, with a circulation of 100,000, by the Feminist Majority Foundation (FMF), another liberal group. Its co-founder, Eleanor Smeal, was a president of NOW. By the time the FMF was founded, in 1987, opinion polls showed that 56% of U.S. women considered themselves feminists. The organization conducts research, education and training program to influence policy and supports grass-roots and student activism for women’s equality, reproductive health, social justice and nonviolence. It also supports worker union rights, pay equity and an end to sweatshops.

FMF generally supports the Democratic Party, intervenes in the electoral process and endorses liberal pro-woman politicians and legislation. It has also set up a national network of campus affiliates to promote its liberal feminist outlook and strategy [7].

Another important liberal group, still active today, is the National Women’s Political Caucus, founded in 1971 by Gloria Steinem and others to help elect women to public office. Addressing the founding meeting of the NWPC, Steinem said: “This is no simple reform. It really is a revolution. Sex and race, because they are easy visible differences, have been the primary ways of organizing human beings into superior and inferior groups, and into the cheap labor on which this system still depends. We are talking about a society in which there will be no roles other than those chosen or those earned. We are really talking about humanism.”

While liberal feminists occasionally used this sort of radical rhetoric for sweeping social equality—even revolution—as we have laid out above, their ideology and program were solidly reformist in orientation. Other trends criticized the limited horizons of this brand of feminism, and became significant forces on college campuses at the grassroots level.

Radical feminism and women’s liberation

Radical feminism emerged from several sources including the feminist wing of the New Left in the later 1960s. It was the current of the mass movement that was developed mostly by young, single women, many of whom were working low-paying day jobs to support their movement work. Many were college educated as well, and had exposure to a wide spectrum of radical ideas and movements percolating on college campuses. They gained their activist experience—direct action, mass protest and community organizing—in the civil rights movement, especially the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the campus-based New Left of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and in anti-Vietnam war activism.

Many rejected electoral politics as a means of attaining their goals. It was this wing of the feminist movement that coined the word “sexism” [8]. Radical feminists identified their movement as “women’s liberation,” a name that ultimately took hold in the public mind to describe the larger women’s movement.

It must be noted that in the beginning of the Second Wave in the mid-’60s, many left-wing men in these various Sixties organizations, such as aforementioned SDS and SNCC harbored patriarchal attitudes toward movement women, and put them down and mocked their demands for total equality. The women did not back down. They built their own dynamic movement and by the end of the 1960s most male leftists (though not all) in the various components of the uprising accepted or championed women’s equality. That was a big victory, and it has lasted in the political left. Here are two examples of male chauvinism in the Sixties written by movement women:

Lindsey German provides this gem in an article in Counterfire, Feb. 2, 2013:

The background to the emergence of the women’s movement in the U.S. in the late ‘60s was a level of sexism and indifference [within the movements] to the question of women which is quite shocking to look back on. The student movement was quite disconnected from the Old Left … Women were told that their oppression was of the least importance, and told so in the most contemptuous and elitist way. At the National Conference for the New Politics held in August 1967, where a radical minority of women tried to formulate demands on women’s liberation, drawing on the politics of black power, they were derided by most of the men at the conference. [Radical feminist] Shulamith Firestone was patted on the head by one of the male leaders and told ‘move on little girl; we have more important issues to talk about here than women’s liberation.’ Such experiences shaped the early women’s movement, which defined itself as dissatisfied with the behavior of the male left.

Frances M. Beal from Third World Women’s Alliance New York wrote in 1969:

Unfortunately, there seems to be some confusion in the Movement today as to who has been oppressing whom. Since the advent of black power, the black male has exerted a more prominent leadership role in our struggle for justice in this country. He sees the system for what it really is for the most part. But where he rejects its values and mores on many issues, when it comes to women, he seems to take his guidelines from the pages of the Ladies Home Journal.

Women’s liberation rebelled against subordination in the mass movement and fought for equality and for recognition of women’s concerns within the movement, as well as for women’s rights in the larger society. For them, equality with men in an unequal and racist society was too small a goal. They rejected male status and achievement as the standard to which women should aspire. They took on issues dealing with housework, interpersonal relationships, sexual relations, family arrangements, as well as inequality and injustice in the larger world.

In an interview for this book [Women fight back!], Amy Kesselman, feminist historian and founding member of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, remembers the origins of the CWLU and describes how women came together in the early years of women’s liberation:

Our group emerged from a conference put on by the National Conference for New Politics, which was in 1967. There were some thoughts of a left third party, which didn’t materialize. A group of us started talking about women’s issues being part of the left and we came up with some things that we wanted to incorporate into whatever document emerged from this conference. Shuli Firestone went up to say that we’d like to present this, and she was told that they had more important things to do. So we started meeting at this conference and came up with a bunch of ideas and soon after formed a group called the West Side Group. We were all left-identified and had been involved in the antiwar and civil rights movements and were full of pent-up ideas…

When I was active in the antiwar movement, the men in that movement—we had a sit-in and there were nine men and me on the steering committee—and I felt sort of trivialized and challenged and invisible and I think a lot of people felt that way. There were a number of things that were written that expressed those feelings. So we had a lot to say. We absolutely thought of ourselves as part of the left, but we also felt that we needed to have an independent women’s movement, so that we could be in coalitions with other groups, but we would control our own movement. And not everybody felt that way…

The group wrote a play. We were going to start an independent women’s movement, a women’s union in Chicago, and there were women on the left who were against it and we were afraid they were going to subvert the conference, so we made this play to bring people together. And it worked! So we started the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union. Part of the inspiration for the Chicago union was from the Vietnamese. One of the women in our group had represented the peace movement on a trip to Vietnam and met the women in the Vietnamese women’s union. She was very impressed about the importance they felt in having an independent women’s organization. And she brought that back.

We made a couple of mistakes though. One was that we felt it was important, since we had experienced having our issues treated as secondary, to focus on women’s issues and experiences. We were worried about women for whom the experience of being a woman was not the primary focus. And I think we did not understand how other groups of women could not put gender as primary, how they had to look at their identities through race and class. So we talked a lot about wanting to connect with African American women and Latina women, but we did not understand that they couldn’t place gender above race….

The other mistake is that we developed theory and consciousness-raising groups based on our experience, which didn’t represent everybody’s experience, although we talked about it as a universal experience. So we learned that that we were not going to be able to create an inclusive movement if we insisted that everybody put gender first….

We certainly tried very hard to connect with women of color and always saw class as important but felt like the theory and practice that we were developing needed to be incorporated into a broad left that addressed every-body’s issues.

Unlike the liberal feminists, radical feminists believed that only a total transformation of society, and not elections or reforms within the existing system, could bring about real freedom for women and ensure that the differences that existed between women and men did not lead to oppression.

The radical feminist trend in the women’s liberation movement opened up many new lines of theoretical inquiry, many of which were quite provocative and stimulating, and helped lay bare the sexist stereotypes that pervaded society in every area [9]. Feminist scholar Christine Stansell wrote, “Women’s liberation generated countless pressure points of agitation, a myriad of ad hoc campaigns to change sexual mores, manners, men’s expectations of women, women’s expectations of themselves, and the very language of gender” [10].

While radical feminists had diverse views among themselves, as a trend they moved away from Marxism and class analysis. Like the socialist and communist feminists, they believed in the necessity for a radical change of the society, but they saw their primary enemy as patriarchy and male supremacy, not capitalism, and women’s oppression as the primary oppression (as opposed to class exploitation or national oppression). Some promoted a view that men had primarily used biological differences to overthrow matriarchy and institute patriarchy, and this remained the core of women’s oppression.

Among their solutions to women’s oppression was a current that promoted separation from men. Despite this current’s origins in the left, a strong thread of anti-communism, along with opposition to leaders and to hierarchical forms of organization, developed within it.

The radical feminists largely took the form of small collectives, with very intense internal dynamics that produced many splits and only a few organizations that have survived to the present.

At the same time, their influence on feminist thought and culture was profound. A key organizer and theorist in this trend was Shulamith Firestone (1945-2012). Raised in an orthodox Jewish family, she broke with her family to become a painter and early leader of the radical feminist movement. In 1969 she co-founded Redstockings, which held the first public speak-outs on abortion, and later New York Radical Women. Firestone believed that the oppression of women had its basis in biology itself, and that women would not be truly liberated until they were freed from the biological imperative of giving birth, to be replaced by artificial reproduction outside the womb. She wrote several books, the best known of which was The Dialectic of Sex, which claimed that the sexual class system was the primary social divide. In a way, the splits and factionalism that plagued radical feminism led to Firestone’s own departure from the movement in the early 1970s. She remained isolated from the movement for the rest of her life and suffered from schizophrenia until her death at age 67.

The Marxist feminists contested certain radical feminist views, while often supporting their actions on behalf of women’s liberation. The main Marxist critique explained that it was incorrect to maintain that the fundamental contradiction in society is patriarchy or male supremacy. The Marxist view is that the main problem is capitalist exploitation and oppression, which will be discussed further directly below. Moreover, while biology undoubtedly influenced and gave shape to the overall experience of women’s oppression in patriarchal class society, what primarily gave rise to women’s oppression was the development of private property relations.

Socialist and Marxist feminism

The 1960-75 rebellions resembled a big coming-out party for the political left after years of isolation and government crackdown on dissidents. For feminists, after a decade of intense government and media pressure upon women to cherish the role of a housewife, subordinate to her husband, following gains achieved during World War II, it was a liberation struggle well worth waging.

The U.S political left begins where liberals and the left wing of the Democratic Party leave off. Included in this category are social democrats, socialists, communists, various radicals, anti-imperialists and anarchists.

The left wing of the socialist movement and various communist groups embraced Marxism and several Marxist-oriented feminist formations were quite active during the Second Wave in protests. Among these groups at the time were Radical Women (affiliated with the Freedom Socialist Party), Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, Bread and Roses in Boston, the Combahee River Collective, and others.

The main criticism of Marxism by some feminist organizations during the period of social uprisings was that the theory was ill equipped to fight against gender oppression in the here and now because it held that women’s liberation would arrive when capitalist class society was abolished.

This was called reductionism for “reducing” the oppression of women to a class issue to be resolved by anti-capitalist revolution. Marx argued in the mid-1800s that gender oppression would dissolve when class oppression was defeated. Actually, as soon as the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917, and the Communist Party of China took over in 1949, both quickly extended women’s rights. Socialist revolutions in Korea, Cuba and Vietnam followed suit.

Up into the 1960s the two leading communist organizations in the U.S., the Communist Party and the Socialist Workers Party, tended to subsume resolution of the “woman question” in practice to that of overthrowing capitalism. Smaller and newer Marxist groups already recognized the necessity to fight for reforms to alleviate the plight of women and all oppressed people.

In February of 1970, women members of one such communist organization, Workers World Party, formed an activist and educational female caucus within a party-organized group named Youth Against War and Fascism. The women wrote at the time: “Our caucus is made up of Black, Latin, Asian and white women. We are workers, mothers, and students—gay and straight.” They participated in a multitude of women’s activities and also “educated ourselves while at the same time raising the consciousness and sensitivity of the men in the organization to the oppression of women.”

A leader of Worker’s World Party, Dorothy Ballan, wrote in 1970: “The women’s struggle is not subordinate to the class struggle. It is itself a form of class struggle, especially if consciously conducted against the bourgeoisie” (i.e., against the capitalist class who own most of society’s wealth and means of production).

According to left feminist Barbara Epstein:

In the 1960s and early 1970s the dominant tendency in the women’s movement was radical feminism. At that time the women’s movement included two more or less distinct tendencies. One of these called itself Socialist Feminism (or, at times, Marxist Feminism) and understood the oppression of women as intertwined with other forms of oppression, especially race and class, and tried to develop a politics that would challenge all of these simultaneously. The other tendency called itself Radical Feminism. Large-R Radical Feminists argued that the oppression of women was primary, that all other forms of oppression flowed from gender inequality. Though the liberal and radical wings of the women’s movement differed in their priorities, their demands were not sharply divided…

The radical feminist vision became stalled, torn apart by factionalism and by intense sectarian ideological conflicts. By the latter part of the 1970s, a cultural feminism, aimed more at creating a feminist subculture than at changing social relations generally, had taken the place formerly occupied by radical feminism. … Ordinarily, such sectarianism occurs in movements that are failing, but the women’s movement, at the time, was strong and growing. The problem was the very large gap between the social transformation that radical feminists wanted and the possibility of bringing it about, at least in the short run.

I think that radical feminism became somewhat crazed for the same reasons that much of the radical movement did during the same period. In the late 1960s and early 1970s many radicals not only adopted revolution as their aim but also thought that revolution was within reach in the United States. Different groups had different visions of revolution. There were feminist, black, anarchist, Marxist-Leninist, and other versions of revolutionary politics, but the belief that revolution of one sort or another was around the corner cut across these divisions. The turn toward revolution was not in itself a bad thing; it showed an understanding of the depth of the problems that the movement confronted. But the idea that revolution was within reach in the United States in these years was unrealistic” [11].

As Epstein indicates above, the belief in pending revolution generated intense enthusiasm for organizing, militancy in the streets and stimulating theoretical discussions about how patriarchy could actually be eliminated—qualities that are often lacking today. To the extent that revolutionaries developed an unrealistic sense of immediate revolution, however, this made the movement’s decline more difficult to endure, leading to widespread disappointment and demoralization.

Writer, investigative journalist and feminist Barbara Ehrenreich is one of the most well-known advocates of socialist feminism, especially for her 1976 essay “What is socialist feminism?” The essay appeared in the publication of the social democratic New American Movement, which was hostile to Marxist-Leninist parties. In it she wrote:

We have to differentiate ourselves, as feminists, from other kinds of feminists, and, as Marxists, from other kinds of Marxists. …

The trouble with radical feminism, from a socialist feminist point of view, is that it doesn’t go any farther. It remains transfixed with the universality of male supremacy—things have never really changed; all social systems are patriarchies; imperialism, militarism, and capitalism are all simply expressions of innate male aggressiveness. And so on… The problem with this, from a socialist feminist point of view, is not only that it leaves out men (and the possibility of reconciliation with them on a truly human and egalitarian basis) but that it leaves out an awful lot about women. For example, to discount a socialist country such as China as a ‘patriarchy’—as I have heard radical feminists do—is to ignore the real struggles and achievements of millions of women…

As feminists, we are most interested in the most oppressed women—poor and working-class women, third world women, etc., and for that reason we are led to a need to comprehend and confront capitalism. I could have said that we need to address ourselves to the class system simply because women are members of classes. But I am trying to bring out something else about our perspective as feminists: there is no way to understand sexism as it acts on our lives without putting it in the historical context of capitalism.”

Ehrenreich went on to criticize “mechanical Marxists” or “economic determinists” who view capitalism strictly through an economic lens while “We, along with many, many Marxists who are not feminists, see capitalism as a social and cultural totality. … We have room within our Marxist framework for feminist issues which have nothing ostensibly to do with production or ‘politics,’ issues that have to do with the family, health care, ‘private’ life” [12].

Writing in Monthly Review in January 2011, Marxist Richard Levins noted:

Feminism is a refreshing influence on Marxism. Early feminist writings in the 18th and 19th centuries, beginning with Mary Wollstonecraft, called for women’s equality and rejected any religious or biological justification for the subordination of women. They sometimes attributed the suppression of women to a hypothesized patriarchal revolution. This was a view that was carried over into classical Marxism in Engels’s ‘Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,’ which referred to ‘the world historical defeat of the female sex.’ The emergence of bourgeois feminism [in the 1920s] was used to justify the [left’s] rejection of feminism as a diversion from the class struggle. But in the 1940s, a core of strong proto-feminist women emerged in the Communist Party USA just at the time when McCarthyism was making all red organizing difficult. Many of the pioneers of Second Wave feminism in the United States had roots in communist and socialist movements and the unions.

The Marxist-oriented Combahee River Collective issued an important statement on socialism and Black feminism in 1977:

We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products, and not for the profit of the bosses. Material resources must be equally distributed among those who create these resources. We are not convinced, however, that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation. … Although we are in essential agreement with Marx’s theory as it applied to the very specific economic relationships he analyzed, we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.

Jane Cutter, a post-Second Wave Marxist feminist and member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL), said in an interview for this book:

People still need to hear voices that are concerned with building class unity. That’s one of the contributions that was made by leftist feminists. We understand unity—not just among women but also between women and men.

Our movement is not a zero sum game, where if someone gets ahead, someone else falls behind. We need to reject negative and shame-based ways of dealing with each other. It weakens a movement when members are afraid to express their opinions and debate the different ways to move forward. Many Second Wave feminists had lively, passionate debates.

I believe women should care about socialism. The material basis for women’s oppression has its origins in class society. We don’t have to go back to ancient history to see that capitalists are profiting by paying women less, profiting off our unpaid labor that’s necessary for the maintenance of the working class as a whole. Lots of women have no maternity leave and have to go right back to work after giving birth. Women make sacrifices—working part time, taking lower paying jobs with more flexible schedules to be able to take care of their children. They do the unpaid childcare labor and household labor for the maintenance of their families, so that other family members can work and the children will eventually become workers. The system is profiting off of this.

Black feminism

Most activists who called themselves specifically “feminist” in the 1960s were white and middle class [13]. However, the movement for women’s liberation was being organized among all races, and activists published each other’s writings, organized actions and attended meetings together, and influenced each other’s thinking from the beginning.

Black women in large numbers supported the goals of the women’s movement. In a 1971 Harris poll, 60% of African American women said they supported efforts to strengthen women’s status in society, compared to only 37% of white women. In 1972, in the first ever survey to ask directly about the women’s movement, 67% of Black women said they supported “women’s liberation,” compared to 35% of white women [14].

Black women had a complex relationship with the feminist movement, despite being among the most enthusiastic proponents of women’s equality. Their liberation was obviously tied to the liberation of all Black people, shaped by a common historical experience of national oppression and resistance alongside Black men even though the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow affected Black women in particular ways. They had to deal with sexism within the Black liberation movement and with white racism in the feminist movement. Differences between heterosexual and lesbian feminists also appeared in the Black feminist movement, with lesbians assuming leadership of prominent segments of the movement.

Women of color generally criticized radical feminists for their separatist elements and for declaring a universal sisterhood, based on their particular experiences, which indicated a lack of understanding of the different experiences of women from different races and classes. They also rejected the practice of putting gender first, ahead of class or race [15].

Black and white women belonged to both racially mixed and separate organizations and no single organizational form or view could claim hegemony within the movement or any particular sector of women. There were also Third World caucuses within racially mixed organizations. In some of these caucuses issues of economic inequality and class stratification became more prominent [16].

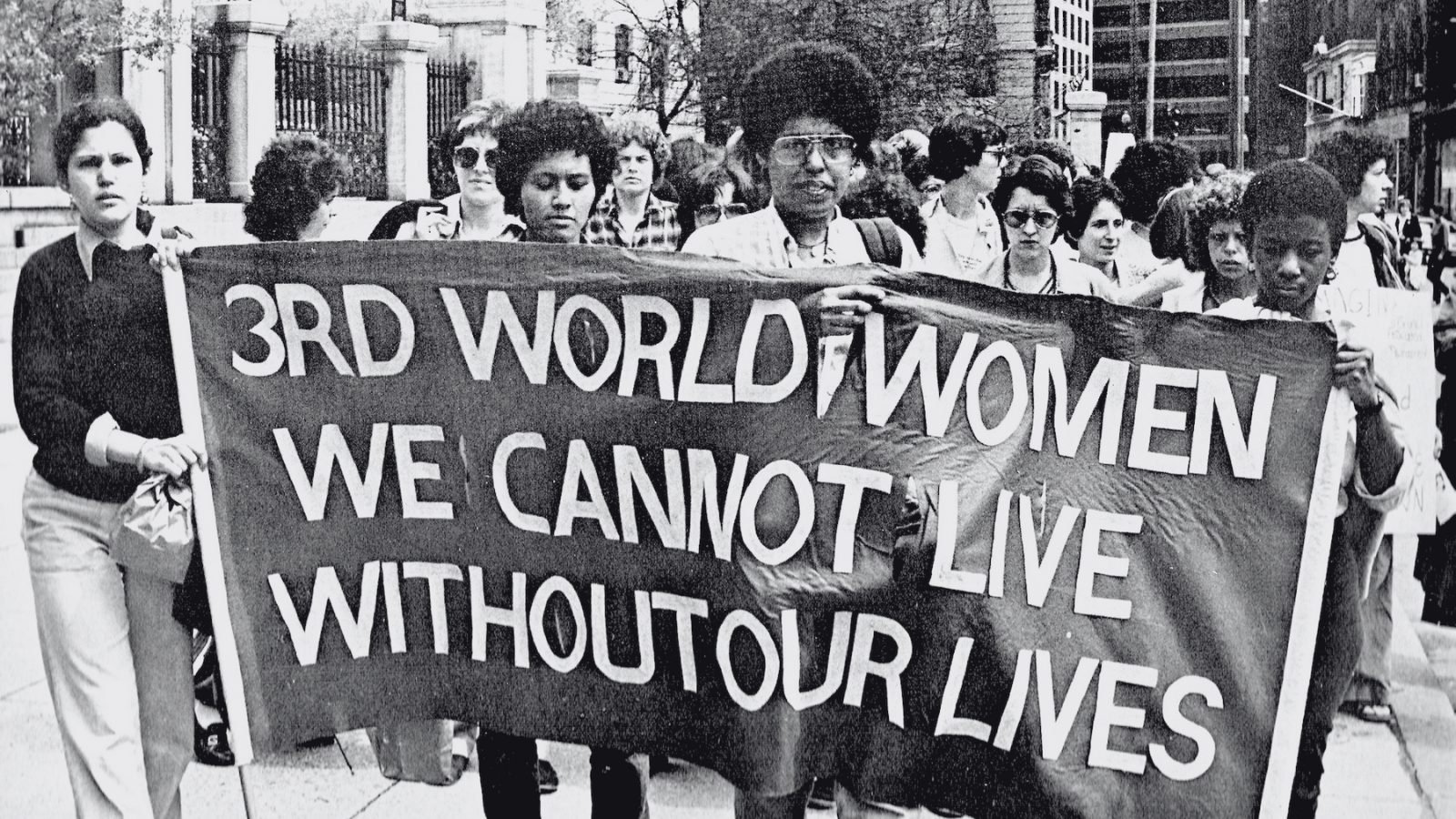

One of the first Black feminist organizations grew out of SNCC’s women’s caucus, which formed in 1968. Merging with a Puerto Rican women’s organization, they called themselves the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA), with an anti-capitalist critique of both the Black liberation movement and the largely white feminist movement. It lasted from 1970 to 1977, after which a sizable number went on to join Marxist-Leninist organizations.

The National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), founded in 1973, sought to combine the fights against racism and sexism. To charges that they were undermining the struggle for Black liberation, they responded that they represented more than half the Black population and that for all Black people to be free, they needed to organize around the needs of Black women. Among the issues they stressed were domestic workers, welfare, reproductive freedom and the situation of unwed mothers. The NBFO operated as a national organization until 1977 [17].

The Combahee River Collective, noted above, was founded by Barbara Smith and others in 1975, when the Boston chapter of the NBFO separated from the national. With Black lesbians in the leadership, the collective presented an early theory of identity politics that consisted of the interlocking identities of gender, race and class, opposed the separatism of segments of radical, Black and lesbian feminism, and promoted coalition politics. The Collective declared itself to be socialist and called for the destruction of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy, as a prerequisite for the liberation of all oppressed peoples. In addition they declared that a socialist revolution must also be feminist and antiracist [18].

Asian American feminism

Asian American women formed grassroots groups throughout the country.

Many Asian American women felt marginalized within the mainstream feminist movement. They struggled against stereotypes and what they felt was the lack of interest among white feminists in learning about the issues of importance to Asian American women. Like many Black feminists, Asian American women stressed the importance of combating racism as well as sexism, both in the larger society and in the mass movement, and in promoting women’s rights in the context of their own communities [19]. Activists established the first Asian American women’s center in Los Angeles in 1972.

Asian American working-class women struggled with issues of immigration as well as workplace discrimination. In the hotel industry, for example, they fought against the wage gap between higher paying skilled jobs and those of cleaners, dishwashers and other low paying and less visible jobs. In the late 1970s they conducted a two-year labor action that won a significant pay increase from management, as well as more respectful treatment from management [20].

Latina feminism

Women in the Latina community were also in motion.

Latina farmworkers, led by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, were active with the United Farm Workers, which involved women from its founding in 1962. These women faced multiple oppressions: As mothers, they watched their children suffer from malnutrition born of poverty. Yet they had to work to earn income for their families and often had to bring their children out into the fields. At home they suffered from domination by their traditional husbands, who asserted the right to rule the family. All of this took place in the context of agricultural workers’ exclusion from New Deal labor legislation that would have established better working conditions, higher pay and benefits. Women were instrumental in organizing and winning farm worker strikes [21].

In 1971 the First National Chicana Conference—La Conferencia de Mujeres por la Raza—was held in Houston, Texas. Six hundred young Mexican American women passed resolutions that asserted their right to a positive attitude toward sex; rejected the Catholic Church as an oppressive institution; and called for the equality of women and men in every respect. They also called for free legal abortion and birth control for the Chicana community, “controlled by Chicanas,” freedom from unwanted medical experiments and double standards about sex, 24-hour child care, and opportunities for political, educational and economic advancement. They also sought equal pay for equal work [22].

Latina women in other parts of the country also led struggles against forced sterilization.

Revolutionary and socialist organizations began to develop and organize in the Chicano and immigrant communities as well, considerably to the left of the UFW.

Lesbian feminism

Lesbians have had a long history of activism in the women’s movement. Unlike other movement activists, their very being at the time was illegal and marked by public ostracism. Laws prohibiting sexual acts between consenting adults of the same sex were in force in every state until 1962. In some states it was even a violation to wear the clothing of the opposite sex. Only in 2003 did the Supreme Court, in striking down Texas’ “sodomy” law, rule in essence that all such state laws violated due process of consenting adults [23]. The Supreme Court’s freedom to marry decision did not arrive until June 26, 2015.

The Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian rights organization, was founded in San Francisco in 1955 by four lesbian couples, with the goal of overcoming social isolation and prejudice, and promoting equality, education, research, and changes in penal codes as they pertained to homosexuality [24]. The DoB described itself as “A woman’s organization for the purpose of promoting the integration of the homosexual into society” [25]. It lasted 14 years, during which time it published a magazine called The Ladder, which was a communications link for many lesbians. A number of readers and members joined the feminist uprising in the mid-’60s.

The mass movements gave impetus to the growing movement for lesbian and gay rights, but even within the feminist movement, lesbians had to fight to have their concerns recognized. They also had to fight against the male dominated gay liberation movement, which marginalized lesbians.

The lesbian and gay liberation movement reached a turning point with the Stonewall rebellion, a historic fight-back action against police repression in June of 1969 at a gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village. Police raids against lesbians, gays, drag queens and transgender people were common at the time, but the patrons of the Stonewall on that evening had had enough.

Night after night, patrons and their allies engaged in violent struggle against the police, as they also sought legitimate and legal places to meet. The larger community was divided; there was some support but also rejection and opposition toward people who were considered outcasts from “respectable society.” Stonewall propelled a whole generation of struggle, which has not ended to this day, and has been commemorated annually in Pride marches all across the country and Pride caucuses within unions and the AFL-CIO, called “Pride at Work.”

As the more liberal feminists rejected open lesbianism, more radical feminists pushed it forward in actions and in new theory. NOW changed its attitude toward lesbians in 1971. Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, founders of the DoB, were NOW members and Martin was the first out lesbian elected to its national board. (Lyon and Martin were also the first same-sex couple to marry in San Francisco after 50 years of commitment.)

Radicalesbians, an organization of “women-identified women,” called lesbians the true feminist radicals [26]. They regarded lesbianism as more of a political choice than a predetermined sexual orientation, a stance that was challenged both within and outside the feminist movement. Others turned to separatism, not only from men but also from heterosexual feminists.

Some early radical lesbians saw heterosexuality as key to male-dominated society and patriarchy and believed that it was necessary to embrace lesbianism in order to overthrow the misogynist social order and create a more just society. They also sought to change patriarchal culture, creating new forms of language (womyn, wimmin) and religion (paganism, goddess worship), as well as engaging in creative and bold direct action, founding arts and performance programs and women’s bookstores, and laying the groundwork for new gender theories in the budding women’s studies discipline [27].

Among the early creative forces of this movement were poets Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich; Barbara Smith, socialist feminist organizer and co-founder of the Combahee River Collective; and theologian Mary Daly.

In the aggregate, lesbian activists contributed significant energy and resoluteness to the feminist movement and they were strengthened in turn by the larger feminist movement. They played a key role in fighting against violence against women and for reproductive rights; created LGBTQ centers in cities across the country for education, social and cultural events and community organizing; fought against discrimination in the military, in educational and religious institutions, and in business; pushed for recognition of lesbian unions, leading up to the marriage equality movement; and fought against discriminatory laws.

Feminist theory and activism contributed to expanded visions of gender identity that are continuing to develop in the current LGBTQ movement, which has both expanded and challenged certain aspects of feminist thought.

Labor feminism

As the women’s movement grew in the 1970s, labor feminists worried that the concerns of poor and working women would be set aside. Along with Black women, working-class feminists were among those who differed with liberal feminism’s claims of universal sister-hood. With different class and racial backgrounds, experiences, relationships with and attitudes toward men, positions in their communities, and overall political orientations, many activist women rejected the claims of the mainstream feminism movement to represent all women. Many also rejected what they saw as the movement giving short shrift to the caregiving and “self-sacrifice” parts of women’s lives. Instead, these women valued these aspects of their lives and wanted them to be recognized and valued by the movement [28].

At the same time, working-class women, while often excluded from popular accounts of the mass women’s movement, were inspired by the movement to open up opportunities for women in the trades and other nontraditional occupations. As “Sisters in the Brotherhoods” tells it: “They faced daunting obstacles entering these occupations. On the job they endured unrelenting, often vicious harassment. They also received support from men who taught them their trades and helped them navigate unfamiliar territory” [29].

Individual women got jobs as firefighters, carpenters, electricians, mechanics and union organizers. They were helped by such organizations as Nontraditional Employment for Women (NEW), which was founded in 1978 to help break gender barriers in skilled unionized trade jobs; CLUW, and several unions [30]. In particular, the UAW and UE committed themselves to training women and opening up their hiring practices, bargained for benefits for women, and worked to combat sexism within the union. Union women fought for pay equity and for policies that would relieve them of the “double day,” the unpaid second shift of housework and childcare [31].

References

[1] Friedan, The Feminine Mystique.

[2] Nicholson, ed., The Second Wave, 2.

[3] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 1945-2000, 11-12, 66-69.

[4] Ibid., 71.

[5] Lerner, Black Women in White America, 599 (see chap. 4, n.14).

[6] Ibid.

[7] See this article.

[8] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 16-17; Stansell, The Feminist Promise, 234-236.

[9] Nicholson, The Second Wave, 2.

[10] Stansell, The Feminist Promise, 222.

[11] Epstein, “What Happened to the Women’s Movement?” Monthly Review 53, no. 1. Available here.

[12] Ehrenreich, “What is Socialist Feminism?” Available here.

[13] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 26.

[14] Mansbridge, “How Did Feminism Get to Be?” American Prospect. Available here.

[15] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 27.

[16] Mansbridge, How Did Feminism Get to Be?

[17] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 121-124.

[18] Eisenstein, ed., Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, 362-372.

[19] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 142-146.

[20] Ibid., 155-157.

[21] Ibid., 19.

[22] Ibid., 104-105.

[23] Ibid., 11.

[24] Ibid., 58-59.

[25] “Daughters of Bilitis.” Available here.

[26] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 101-103.

[27] Wilson, “1970s Lesbian Feminism,” The Feminist Ezine. Available here.

[28] Cobble, Feminism Unfinished, 62.

[29] “Sisters in the Brotherhoods.” Available here.

[30] ibid.

[31] MacLean, The American Women’s Movement, 8-9.

Featured photo: From The Combahee River Collective’s pamphlet Six Black Women: Why Did They Die? Available here.