This article originally appeared on Black Agenda Report on July 24, 2024.

In 1968, the late activist and Black Studies scholar Robert L. Allen published a slim, two-part pamphlet called “The Dialectics of Black Power.” The first part of the pamphlet, titled “the politics of black power,” addresses the confusion concerning the definition of a term that Allen mused, “means many things to many people.” To remedy these ambiguities of meaning, Allen identifies five elements of Black power and succinctly traces its history from its origins as a militant response to the civil rights movement, to its emergence as a platform for cultural nationalism, to its transformation by the late 1960s into a program for “black elite control of the black community,” propagated by foundation and corporate interests.

The second section of Allen’s pamphlet examines the outside influences driving those historical transformations. It is here that we can understand the “dialectic” of Allen’s title. The historical transformations of the meanings and practice of Black Power do not derive from nothing. Instead, they emerge from those forces of reaction, co-optation, and counter-revolution that have tirelessly worked to neutralize Black Power’s radical demand, pushing for mere social reform–and advocating Black representation instead of Black revolution.

The title of the second section is “the ford foundation and Black Power.” Allen identifies the Ford Foundation, a multi-billion dollar granting agency whose capital base was derived from dividends from Ford Motor Co. shares, as a major agent in enabling the dialectical transformations of Black Power. As the Foundation’s income grew alongside “racial unrest” in the US, its directors sought to redirect their funds towards national, and in some cases international, social issues. Ford developed a strategy of co-opting members of the Black political elite through grants and fellowships, allowing the Black elite to anoint themselves as both experts on and leaders of the Black community. The Black elite, and their Ford-funded organizations, effectively neutralized insurgent, autonomous, grass-roots movements by stepping in as neo-colonial administrators, always reporting back to their white masters.

Allen writes: “Working directly or indirectly through these organizations, as well as other national and local groups, the Foundation hopes to channel and control the black liberation movement in an effort to forestall future urban rebellions.”

Today, we can see how this model of representation, co-option, and Black elite supplication and selling out to white power has expanded far beyond Ford and far beyond the borders of the United States. The examples are legion: Black academics are granted foundation cash to study (that is, to surveil and catalog) Black social movements as a response to Black Lives Matter. “Black internationalist” scholars are awarded prizes of blood-washed cash by zionist foundations to buy scholarly silence on the genocide of the Palestinian people . Kamala Harris is undemocratically announced as the Democratic candidate for President of the United States as a kind of apotheosis of imperialist intersectionality. Harris is Black. Indian. A woman. But, more importantly, she is also a cop, a capitalist, a zionist, and an imperialist whose only interest in Black, Indian, and women’s liberation is to undermine and destroy it. Unless, of course, liberation somehow means the enriching of the global elite.

“The Dialectics of Black Power ” was originally published as a series of weekly articles in the independent radical journal The Guardian, where Allen was a staff writer. Its arguments formed the basis of Allen’s classic treatise Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytical History (1969). In tribute to Allen’s memory and the continuing relevance of his scholarship, we reproduce “the ford foundation and Black Power” below.

The Ford Foundation and Black Power

Robert L. Allen

The politics of the Ford foundation

One of the most important though least publicized organizations in the civil rights movement today is the multi-million dollar Ford Foundation.

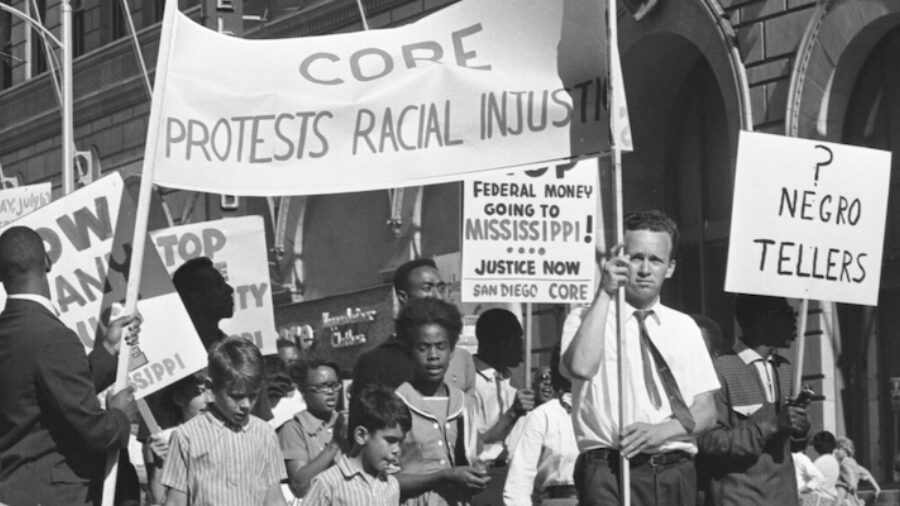

Housed in an ultra modern headquarters building on East 43rd St. in New York City, the Foundation plays a key part in financing and influencing almost all major civil rights groups, including the Congress of Racial Equality, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, National Urban League, and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Working directly or indirectly through these organizations, as well as other national and local groups, the Foundation hopes to channel and control the black liberation movement in an effort to forestall future urban rebellions.

The Foundation catalogs its programs and grants under such headings as: public affairs, education, science and engineering, humanities and the arts, international training and research, economic development and administration, population, international affairs, and overseas development. The list reads like a selection from the courses offered by a good liberal arts college . Race problems are listed as a subclass of public affairs.

Under the leadership of McGeorge Bundy, former Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, the Ford Foundation in 1966 made an important decision to expand its activities in the black freedom movement. Prior to that time the Foundation had limited its activities among black Americans to traditional educational efforts and research projects designed to bring more blacks into the middle-class mainstream. The 1966 decision was a direct response to urban revolts, which were growing, both in size and frequency. It was a logical extension of an earlier decision to actively enter the political arena.

Established in 1936 by Henry and Edsel Ford, the Foundation initially made grants largely to Michigan charitable and educational institutions. According to its charter, the purpose of the organization is “To receive and administer funds for scientific, educational, and charitable purposes, all for the public welfare, and for no other purposes . . . ” Most of the Foundation’s income was, and still is, derived from its principal asset, class A nonvoting stock in the Ford Motor Co. In 1950, serving as a tax-exempt outlet for war profits, the Foundation expanded into a national organization, and its activities quickly spread throughout the U.S. and some 78 foreign countries.

In a special Board of Trustees’ report prepared at that time, the Foundation announced its intention to become active in public affairs by “support[ing] activities designed to secure greater allegiance to the basic principles of freedom and democracy in the solution of the insistent problems of an ever changing society.” This vague mandate, which at first meant little else than underwriting efforts to improve public administration, was gradually brought into sharper focus as the Foundation experimented with new programs.

Foundation ‘interest’ shifts

In 1962, Dyke Brown, then a vice president with responsibility for public affairs programs, could write that the Foundation’s interest had “shifted from management and public administration to policy and the political process.” He added that these programs “tended to become increasingly action-rather than research-oriented” which meant that the Foundation had to be prepared to take certain “political risks.”

How an official of a supposedly independent, non-partisan, nonpolitical philanthropic institution could justify such a statement can be understood simply by examining how the Foundation views its relationship to the major political parties and the government. Simply stated, the Foundation sees itself as a mediator which shows Democrats and Republicans their common interests and reasons for cooperating. For example, the Foundation has sponsored many “nonpartisan” conferences of state legislators and officials with the purpose of stressing “nonpolitical” consideration of common problems. Such bipartisan activities insure the smooth functioning of state and local political machinery by reducing tensions and other sources of conflict which might upset the U.S. corporate society.

The role of the private foundation vis-a-vis the government was made explicit by Henry T. Heald, Bundy’s predecessor as president of the Ford Foundation, in a speech at Columbia University on March 5, 1965. “In this country, privately supported institutions may serve the public need as fully as publicly supported ones,” Heald said. “More often than not, they work side by side in serving the same need.”

Heald went on to state that, through their activities, private foundations can serve as a kind of advance guard, paving the way for later government activity, not only in the fields of education and scientific research but also in the area of “social welfare .” Thus, the private foundation can act as an instrument of social innovation and control in areas which the government may not be able to penetrate.

Bundy/Kennedy

This is the line of Foundation thinking which confronted Bundy as he stepped from his “little State Department” in the White House at the beginning of 1966. And Bundy was ideally suited to developing further this way of thinking. From his years of serving the U.S . power structure, Bundy had developed a keen appreciation of the complexities involved in political manipulation and the seemingly contradictory policies which often must be pursued simultaneously in order to obtain a given end.

Bundy summarized his political outlook in an article entitled “The End of Either/Or” published in January, 1967, in the magazine Foreign Affairs. In the article Bundy first asserts that foreign policy decisions are related to U.S. national interests, although he does not state who determines these interests or sets priorities. He then goes on to criticize those who view foreign policy options in terms of simple extremes. “For twenty years from 1940 to 1960 the standard pattern of discussion on foreign policy was that of either/or : Isolation or Intervention, Europe or Asia, Wallace or Byrnes, Marshall Plan or Bust, SEATO or Neutralism, the U.N. or Power Politics, and always, insistently, anti-Communism or accommodation with Communists.”

The world is not so simple, Bundy wrote, and “with John F. Kennedy we enter a new age. Over and over he [Kennedy] insisted on the double assertion of policies which stood in surface contradiction with each other: resistance to tyranny and relentless pursuit of accommodation; reinforcement of defense and new leadership for disarmament; counter-insurgency and the Peace Corps; openings to the left but no closed doors to the reasonable right; an Alliance for Progress and unremitting opposition to Castro; in sum, the olive branch and the arrows.”

Bundy learned that it is necessary to work both sides of the street in order to secure and expand the American empire. Thus he was a staunch supporter of Kennedy’s and Johnson’s war policies in Vietnam while at the same time stressing the necessity of keeping channels open to the Soviet Union.

Such a man was ideally suited to work with and aid civil rights groups, including black power advocates, while at the same time the government is arming and preparing to use force to suppress the black communities. The seeming contradiction here, to use Bundy’s term, is only a “surface” manifestation.

The Ford Foundation’s interest in the civil rights movement was announced by Bundy at the 1966 annual banquet of the National Urban League in Philadelphia. “We believe,” he said, “that full domestic equality for all American Negroes is now the most urgent concern of this country.” More specifically: “the quality of our cities is inescapably the business of all of us.” Many whites recognize, he continued, “that no one can run the American city by Black Power alone,” the reason being, he suggested at a later point, that urban black majorities would still be faced with white majorities in the State Houses and the U .S . Congress . But if the blacks burn the cities, then, he stated, it would be the white man’s fault and “the white man’s companies will have to take the losses .” White America is not so stupid as not to realize this, Bundy assured the Urban Leaguers.

Another important development in the summer of that year was an unpublicized meeting between Foundation officials and representatives of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, and other civil rights groups . The meeting took place at Foundation headquarters in New York, and reportedly the discussion centered on how to deal with black power and isolate the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a group which was becoming increasingly militant.

In early 1967 the Foundation made grants of several hundred thousand dollars to the NAACP and the Urban League. A few months later the Foundation gave $1 million to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s new National Office for the Rights of Indigents. But for the Foundation’s purposes, these groups were less than satisfactory since there was serious doubt as to how much control they exercised over the young militants and frustrated ghetto blacks who were likely to be heaving molotov cocktails during the summer. If its efforts to keep the lid on the cities were to succeed, the Foundation must somehow attempt to penetrate militant organizations which were believed to wield some influence over the angry young blacks of the ghettos.

Similar to Rand Corp.

The first move in this direction occurred in May, 1967, when the Foundation granted $500,000 to the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC), a newly created organization in New York with a militant-sounding program headed by Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, a psychology professor who at one time was associated with Harlem’s anti-poverty program . When it was organized the previous March, MARC announced that its purpose was “to pioneer in research and action on behalf of the powerless urban poor in Northern metropolitan areas.” Interestingly, in a brochure MARC compared itself with the semi-governmental RAND Corporation which does research for the air force. The difference between the two, according to the brochure, is that MARC is not associated with the government, nor is it limited to research. It is also an action organization.

One of the MARC’s first actions was to name Roy Innis, then chairman of the militant Harlem chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), as its first civil rights “fellow-in-residence.” The May 11 announcement also stated that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Rev. Andrew Young, one of King’s chief aides, had “agreed to take part in the fellowship program.”

Innis, now associate national director of CORE, received a six-month fellowship. “The civil rights fellowships,” wrote The New York Times May 12, “are designed to give the leaders an opportunity to evaluate their programs and tactics and undertake long-range planning.” MARC’s staff was to aid the leaders in their studies, and the fellows were to draw salaries equal to those they received from their organizations or from private employment.

Clark said he had also discussed fellowships with Floyd McKissick, national director of CORE; Stokely Carmichael, then chairman of SNCC; Whitney Young of the Urban League; and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP .

MARC’s secret meeting

MARC’s next move was to call a secret meeting of civil rights leaders for May 27. The meeting was held at the home of Dr. Clark. Subsequently, another such meeting was held June 13 at a Suffern, N.Y., motel between Clark and leaders of nine major civil rights groups. At the conclusion of that meeting, Clark announced a joint effort to calm Cleveland’s racial tension. He said the “underlying causes of unrest and despair among urban ghetto Negroes, as well as clear indications of their grim, sobering, and costly consequences, are found in classic form in Cleveland.”

Clark did not mention that the Ford Foundation had been trying to “calm” Cleveland since 1961 by financing various local research and action projects. But Cleveland blew up in 1966 and further rumblings were heard in the early spring of 1967.

Clearly, a new approach was needed in Cleveland, and the stage was set for the Foundation’s first direct grant to a militant group-the Cleveland chapter of CORE. The Foundation announced on July 14 that it was giving $175,000 to the Special Purposes Fund of CORE to be used for “training of Cleveland youth and adult community workers, voter registration efforts, exploration of economic development programs, and attempts to improve program planning among civil rights groups.” In explaining the grant, Bundy said that Foundation staff and consultants had been investigating Cleveland “for some months.” In fact, he said, “it was predictions of new violence in the city that led to our first staff visits in March.”

“Businesslike” arrangement

Apparently realizing that the grant might give the impression of a close relationship developing between the Foundation and CORE, Bundy added: “The national officers of CORE have dealt with us on this matter in a businesslike way, and neither Mr. Floyd McKissick nor I suppose that this grant requires the two of us-or our organizations-to agree on all public questions . It does require us both to work together in support of the peaceful and constructive efforts of CORE’s Cleveland leadership, and that is what we plan to do.”

It must be said that CORE was vulnerable to such corporate penetration. In the first place, they needed money. Floyd McKissick in 1966 had become national director of an organization which was several hundred thousand dollars in debt, and his espousal of black power scared away potential financial supporters.

Secondly, CORE’s militant rhetoric but reformist definition of black power as simply black control of black communities appealed to foundation officials who were seeking just those qualities in a black organization which hopefully could tame the ghettos. From the Foundation’s point of view, old-style moderate leaders no longer exercised any real control while genuine black radicals were too dangerous. CORE fit the bill because its talk about black revolution was believed to appeal to discontented blacks, while its program of achieving black power through massive injections of governmental, business, and Foundation aid seemingly opened the way for continued corporate domination of black communities by means of a new black elite.

Surprisingly, to some, CORE’s program, as elaborated by Floyd McKissick last July, is quite similar to the approach of the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC) Both organizations see themselves as intermediaries whose role is to negotiate with the power structure on behalf of blacks and the poor generally. Both suggest that more government and private aid is necessary and both seek to gain admission for poor blacks and whites into the present economic and political structure of U.S. society. McKissick, who last fall became the second CORE official to accept a MARC fellowship, criticized capitalism but only because black people are not allowed to participate fully in it. The Ford Foundation could apparently view its grant to Cleveland CORE as a success. There was no rebellion in Cleveland, and, as the Jan. 6 issue of Business Week suggested, money given to a black militant group helped to elect a Negro moderate as mayor.

Moving into Harlem

Having proved successful in Cleveland, the Ford Foundation began exploring other ways of ensuring urban tranquility. In March, 1967, following a year of demonstrations and boycotts centering around community control of schools, the Harlem chapter of CORE proposed that an independent school board be established for Harlem. According to the proposal, integration had failed and the only way to achieve quality education for Harlem’s youth was through community control of its schools. Harlem CORE set up a Committee for Autonomous Harlem School District and began organizing support for its proposal.

The following November, Bundy recommended that New York’s school system be decentralized into 30 to 60 semi-autonomous local districts. Bundy had been named head of a special committee on decentralization at the end of April after the state legislature directed Mayor John Lindsay to submit a decentralization plan by Dec. 1 if the city was to qualify for more state aid. Lindsay insisted that decentralization was “not merely an administrative or budgetary device, but a means to advance the quality of education for all our children and a method of insuring community participation in achieving that goal.”

Bundy’s proposal would allow for not one but possibly several school boards for Harlem. Harlem CORE’s school board committee therefore found itself in the curious position of being on the same side as The New York Times in giving critical support to the Bundy plan, while both the New York City Board of Education and the United Federation of Teachers opposed it.

Although the Bundy plan is still being debated, it again shows the Foundation’s willingness to make small alterations in the local status quo in order to insure tranquility’ while maintaining the overall balance of power.

Detroit says no

The Foundation attempted to play a similar role in its offer of $100,000 to a Detroit black militant group, the Federation for Self-Determination. The federation was set up following the summer, 1967 rebellion and appealed for financial support to the New Detroit Committee (NDC), also organized after the revolt with the purpose of rebuilding and preventing future uprisings. Foundation board member Henry Ford II is also a member of the NDC.

Rivalry developed between the federation and a more moderate group, both seeking funds to reconstruct the black community . The Foundation dealt with the problem by offering both groups $100,000 . But the federation voted to reject the offer because of a stipulation that the spending of the money be supervised by an overseer appointed by the NDC. “Self-determination means black control of black communities,” said Rev. Albert Cleage, head of the federation, in rejecting the money. Interestingly, CORE’s McKissick flew to Detroit to endorse Cleage’s stand.

The Foundation was more successful in its efforts to aid Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and quite possibly partially underwrite King’s plans for massive demonstrations in Washington in the spring of 1968. SCLC had been in financial trouble since King stated his opposition to the Vietnam war last year.

Links with SCLC

Following the summer rebellions King announced plans for a “massive civil disobedience” campaign in major cities in an effort to avert continued urban violence. At the beginning of January it was disclosed that the civil disobedience action will center on Washington, and that SCLC staff members will be assigned to nine cities and six rural areas to mobilize people for the demonstration in the capital. Two days later the Ford Foundation announced a grant of $230,000 to SCLC to be used to train black ministers in urban leadership and help them start local programs to deal with the “crisis in the cities.” Under the terms of the grant SCLC will conduct seminars for about 150 ministers. The seminars are to be held in 15 cities and run in cooperation with none other than the Metropolitan Applied Research Center.

Corporate America signs on

Ford’s pioneering efforts in the black movement and the ghettos were quickly followed by America’s corporatists. Some 50 white-owned corporations helped finance Newark’s Black Power Conference last July. At the end of that month an Urban Coalition-termed the “Anti-Rioters” by Business Week-was organized in Washington. The coalition (Guardian, Jan. 13, 1968) includes big-city mayors, labor officials, business figures, and Foundation personnel (including Henry Ford II). The coalition is nation-wide in scope and its purpose is to aid private industry’s penetration and pacification of the ghettos.

It has become increasingly clear to the corporate elite that where the anti-poverty program had failed in controlling rebellious black communities, perhaps business could succeed. This idea was strengthened by statements from black leaders such as MARC’s.

Kenneth Clark, who declared that “Business and industry are our last hope because they are the most realistic elements of our society.” The National Urban League’s Whitney Young added, at a recent meeting of the National Industrial Conference Board, that “The American business community must work things out with the Negro community in much the same way it worked things out with the labor movement.”

January, 1968.

Excerpted from Robert L. Allen, The Dialectics of Black Power, (New York: The Guardian, 1968). A copy of this pamphlet has been digitized by The Freedom Archives.