Editorial note

The following is the first half of a report by Human Rights Watch was published in 1997 as part of a growing concern amongst human rights agencies and advocates over the legal, moral, and ethical issues involved with the increasing number of super-maximum-security prisons. It focuses on two Indiana prisons: Westville Correctional Facility and Wabash Valley Correctional Facility. Several former and current political and social prisoners contributed to the report. You can read the second half of the report here.

The report is available in plain text here, although organizers with the Liberation Center felt it necessary to format and divide the report into two sections to make it easier to read. When possible, we have corrected grammatical and formatting errors.

There’s no way you can know what it’s like for us in here.

Prisoner, the Maximum Control Facility

If you have an animal in a cage, and you’re constantly provoking him and hurting him and one day you let him out, you’ll have a dangerous animal.

Prisoner, the Secured Housing Unit, Wabash Valley Correctional Facility

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

All prisoners shall be treated with the respect due to their inherent dignity and value as human beings.

Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners

I. Introduction

The management of prisoners who engage in dangerous or disruptive behavior while incarcerated challenges prison authorities worldwide. In the last decade, corrections departments in the United States have increasingly chosen to segregate such prisoners in special super-maximum-security facilities. Although conditions and policies vary somewhat from facility to facility, their common characteristics are extreme social isolation, reduced environmental stimulus, scant recreational, vocational, or educational opportunities, and extraordinary levels of surveillance and control. Prisoners are locked alone in their cells between twenty-two and twenty-three-and-a-half hours a day. They eat and exercise alone. For years, except for the occasional touch of a guard’s hand as they are being handcuffed when they leave their cells, they have no physical contact with another human being.

Prisons in the United States have always contained harsh solitary punishment cells where prisoners are sent for breaking prison rules. But what distinguishes this new generation of super-maximum-security facilities are the increasingly long terms which prisoners spend in them, their use as a management tool rather than just for disciplinary purposes, and their high-technology methods of enforcing social isolation. No longer a matter of spending fifteen days in the “hole,” prisoners classified as dangerous or disruptive can spend years in solitary confinement. Rather than looking for constructive ways to help these prisoners develop the ability to live peaceably with others, correctional systems in the United States have turned with a vengeance to what some call “high-tech cages,” in the pursuit of total security and control.

Human Rights Watch has observed the burgeoning use of super-maximum-security facilities with concern. As human rights groups are well aware, prisons by their nature possess great potential for abuse. That potential is even greater when authorities confront those deemed the most violent and anti-social of the inmate population. In the United States, the trend toward super-maximum-security confinement parallels and is exacerbated by a political climate that encourages ever harsher, more punitive forms of punishment for criminals. With politicians vying for public favor by showing that they are “tough” on crime and prisoners, with the courts reluctant to interfere in correctional policies, and with public scrutiny impeded by distant locations and regulations limiting access, correctional authorities seldom face external pressure to insist that prisoners not be sent unnecessarily or arbitrarily to super-maximum-security facilities, or to ensure that prisoners within them are treated humanely.

Human Rights Watch is particularly concerned that harsher conditions of imprisonment are being inflicted on those prisoners who are least able to cope with them. In the United States, increasing numbers of mentally ill people are being incarcerated. Unable to adjust to the myriad rules and powerful stresses of prison life, mentally ill prisoners often accrue disciplinary records that lead to their placement in super-maximum-security facilities. Indeed, the population of many such facilities includes a high percentage of prisoners with serious psychiatric disorders. For this reason, the impact of super-maximum-security conditions on mental illness is a subject deserving of urgent attention.

Some people in the United States believe that prisoners, especially those who have committed acts of violence while in prison, have forfeited their rights and deserve to be treated, as one Texan warden declared bluntly, “like animals.” Such views betray a profound ignorance of internationally accepted principles regarding the fundamental rights of all human beings-principles to which the United States is legally and historically committed. Besides evidencing little respect for human dignity, such views are also unwise. Most inmates in super-maximum-security prisons will one day be released back into local communities. If these people have been abused, treated with violence, and confined in dehumanizing conditions that threaten their very mental health, they may well leave prison angry, dangerous, and far less capable of leading law-abiding lives than when they entered.

In this report, Human Rights Watch reviews the operation of two super-maximum-security prisons for men operated by the State of Indiana: the Maximum Control Facility at Westville, and the Secured Housing Unit at Carlisle’s Wabash Valley Correctional Facility. We assess the extent to which they comply with the human rights standards contained in international conventions to which the United States is a party and, in so doing, we hope to assist the people and government of Indiana evaluate their legality, wisdom, and impact.

We also hope to contribute to the debate, nationally and internationally, regarding the proper treatment of disruptive and dangerous inmates. The challenge faced by the Indiana Department of Correction to securely and humanely confine these prisoners is shared by correctional authorities throughout the United States and, indeed, throughout the world. The appeal of super-maximum-security prisons is readily understandable. But in corrections, as in other spheres of government, there are no easy solutions. Without guidance and control by principled authorities, super-maximum-security prisons can become as lawless as the prisoners they confine.

Access and Methodology

Human Rights Watch has monitored and reported on prison conditions within the United States since 1980 [1]. For our prison investigations, Human Rights Watch follows a self-imposed set of procedures, the key elements of which include an insistence on interviewing prisoners privately and on viewing all areas of a given facility. Thanks to the cooperation of the Indiana authorities, our inspections of the state’s two super-maximum-security institutions were conducted in accordance with these general rules.

Human Rights Watch originally sought permission to inspect the Maximum Control Complex (MCC), Indiana’s first super-maximum-security facility, in 1993. Our request was made at the urging of local activists and after we had received a steady flow of letters from MCC inmates alleging serious human rights abuses. The initial response of the Indiana Department of Correction (Indiana DOC), then headed by Commissioner Christian Debruyn, was a flat denial of access. The commissioner’s negative response was noted in the press, as well as by local religious, legislative, and civil rights leaders, who urged him to reconsider his decision [2].

In May 1995, after settlement of a class action lawsuit challenging conditions at the MCC and replacement of its superintendent, the commissioner decided to grant access to our investigators, and a visit was arranged for the following month. By that time, a second super-maximum-security facility had opened in Indiana-the Secured Housing Unit of the Wabash Valley Correctional Institution, known as the SHU [3]. Our visit to the MCC convinced us that an investigation of both of Indiana’s super-maximum-security conditions was appropriate, and we visited the SHU the following year, in April 1996. The Indiana DOC granted us unrestricted access to all areas of both facilities, as well as to all the prisoners. (We were not allowed into inmates’ cells for security reasons but were able to enter cells in empty housing sections.) During our first visit to the MCC, we had short conversations through cell doors with approximately forty prisoners, a majority of the MCC population at that time, followed by more extended interviews in private rooms with approximately ten prisoners; our April 1996 visit to the SHU was similar.

In our visit to the SHU, we were struck by the number of severely mentally ill inmates confined there. In July 1997, with the cooperation of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), we returned to the SHU and to the MCC, since renamed the Maximum Control Facility (MCF), with two psychiatrists experienced in evaluating mentally ill inmates. The psychiatrists, one of whom served as a PHR representative, conducted structured interviews that reliably and systematically assess the presence or absence of a broad range of psychiatric symptoms, using a rating scale that accurately evaluates the level of severity of such symptoms-methods that are widely accepted in the psychiatric field. These interviews, which ranged from twenty to forty-five minutes in length, were conducted with fourteen prisoners at the MCF and twenty-seven prisoners at the SHU. Human Rights Watch researchers spoke with several dozen additional prisoners.

During each of our visits, members of the Human Rights Watch delegations also spoke at length with staff members of both facilities, including line officers, supervisory staff, and mental health staff. Herbert Newkirk, the superintendent of the MCF, and Craig Hanks, the superintendent of the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility (of which the SHU is a part), were both extremely cooperative throughout our visits, as were all of the members of their staffs whom we met.

International Human Rights Standards Governing the Treatment of Prisoners

The chief international human rights documents binding on the United States clearly affirm the human rights of people in confinement. Indeed, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the most comprehensive international human rights treaty that the country has ratified, includes provisions explicitly intended to protect prisoners from abuse.

Several additional international documents flesh out the human rights of persons deprived of liberty, providing guidance as to how governments may comply with their international legal obligations. The most detailed guidelines are set out in the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Standard Minimum Rules), adopted by the Economic and Social Council in 1957. Other relevant documents include the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons Under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, adopted by the General Assembly in 1988, and the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners, adopted by the General Assembly in 1990.

It should be emphasized that even though the latter group of instruments are not treaties, they constitute authoritative guides to the content of binding treaty standards and customary international law. In the United States, where international law norms may inform the judicial construction of constitutional provisions [4]. the Standard Minimum Rules have been cited as evidence of “contemporary standards of decency” relevant in interpreting the scope of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, as well as the constitution’s Due Process Clause [5].

Except for the right to life, the most fundamental right of prisoners-and one that is often at risk-is the right not be subject to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. This right is protected by both the ICCPR andthe Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, another treaty to which the United States is a party [6].

Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture defines torture as:

“any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information of a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

Neither treaty expressly defines the phrase “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” The predominant view among international authorities is that such abuse is of a lesser severity than torture, but that no clear line separates the two practices. Rather than clear categories, most experts see a continuum in which a number of factors are relevant, including the nature and intensity of the practice, its purpose, its duration and frequency, and the vulnerability of the victim. What may be torture if continued for an extended period of time, or if practiced upon achild or other vulnerable person, may be prohibited ill-treatment in other circumstances, or may even fall below the minimum level of severity [7].

It is indisputable that torture and other prohibited ill-treatment may involve mental suffering as well as, or instead of, physical suffering [8]. It is also clear that solitary confinement, particularly for long periods and particularly when combined with extreme deprivation of sources of stimulation, may cause mental suffering severe enough to violate international standards [9]. Nonetheless-given the inherent imprecision of the relevant standards, the many factors that must be considered, and the difficulty of measuring mental as opposed to physical suffering-it is no easy matter to determine when permissible disciplinary or administrative policies become prohibited abuse [10].

All observers agree that solitary confinement and regimes of extremely limited social interaction merit extraordinary attention and concern. Because of these conditions’ high potential for abuse, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment-the expert prison-monitoring body associated with the Council of Europe-“pays particular attention to prisoners held, for whatever reason (for disciplinary purposes; as a result of their `dangerousness’ or their `troublesome’ behavior; in the interests of a criminal investigation; at their own request), under conditions akin to solitary confinement” [11]. Besides treaty prohibitions on torture and other ill-treatment, such restrictive conditions may also violate the ICCPR’s rule that “[a]ll persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person” [12].

With regard to disciplinary and other forms of segregation, it should also be noted that the Standard Minimum Rules mandate that discipline and order be maintained with firmness, but with “no more restriction than is necessary for safe custody and well-ordered community life” [13]. In particular, international human right instruments limit the punishments that prison officials can impose on prisoners who commit rule infractions. Besides barring torture and other ill-treatment, they prohibit corporal punishments and the use of physical restraints as punishment [14].

International standards are not only aimed at preventing abuses; they also reflect the consensus of the international community that the period of imprisonment should be utilized to help inmates lead law-abiding and self-supporting lives upon release. The ICCPR, for example, requires that “the reform and social readaptation of prisoners” be an “essential aim” of imprisonment [15]. To this end, “the institution should utilize all the remedial, educational, moral, spiritual, and other forces and forms of assistance which are appropriate and available, and should seek to apply them according to the individual treatment needs of the prisoners” [16].

It should be emphasized, in this respect, that the treatment needs of mentally ill prisoners merit particular attention and care. According to the Standard Minimum Rules, prisoners who suffer from mental diseases or abnormalities “shall be observed and treated in specialized institutions under medical management” [17]. The United Nations has also endorsed principles for the protection of the mentally ill which expressly affirm their right “to be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person” and to be protected from “physical or other abuse and degrading treatment” [18].

Guided by the above standards, Human Rights Watch approached the task of evaluating conditions at the MCF and the SHU with several issues in mind. We investigated the degree of social contact and interaction allowed prisoners; the quality and amount of other sensory, intellectual, physical, and emotional stimuli provided them; the soundness of prisoner selection procedures and the nature of the inmate population that resulted; the length of time prisoners spent in restrictive conditions; the use of excessive physical force against prisoners, as well as other forms of guard harassment and abuse; the punitive use of physical restraints; the psychological impact of conditions, particularly on mentally ill prisoners; the mental health treatment and attention provided; and the quality of transition assistance given to prisoners before release from the facilities. Our focus was to gauge whether, and to what extent, prisoners are held in unduly harsh conditions of social isolation and reduced environmental stimulus for excessive periods of time. It was also to assess whether mentally ill prisoners were being punished, isolated, and otherwise mistreated for psychiatric problems over which they lacked control.

II. Summary and recommendations

In Indiana, as in many states, single cell confinement in harsh conditions in super-maximum-security facilities is justified as necessary for certain inmates for reasons of “security.” Security, however, cannot excuse conditions that are so harmful or repugnant as to constitute torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. As federal district Judge Thelton Henderson trenchantly observed, “Sedating all inmates with a powerful medication that leaves them in a continual stupor would arguably reduce security risks; however, such a condition of confinement would clearly fail constitutional muster” [19].

Prisoners in the MCF and SHU, many of whom are severely mentally ill, are confined twenty-two or more hours a day in solitary isolation in small cells, spend each day utterly idle, are placed in restraints whenever they are escorted from their cells, exercise alone, and remain shackled in front of their families during non-contact visits conducted behind clear partitions. At both facilities-but particularly at the MCF during its early years of operation-prisoners have faced physical abuse, including beatings and unnecessary and excessive use of cell extractions carried out by five-member teams of guards, macings and placement in four-point restraints as punishment.

While cognizant of the Indiana DOC’s legitimate security concerns, we conclude that subjecting prisoners to long periods of confinement in the MCF and the SHU is inconsistent with respect for the inherent dignity of each person. The conditions at these facilities are so extraordinarily harsh and potentially harmful that no person should be subjected to them for unduly lengthy periods of time. Many aspects of the conditions exceed what is required to meet reasonable security goals and are simply punitive. No prisoner, of course, should ever be subjected to physical abuse.

The Indiana DOC is responsible for securely and humanely housing even its most disruptive and dangerous prisoners. It may be that some prisoners are so extraordinarily dangerous that they can only be safely confined in extremely restrictive conditions. The DOC, however, uses procedures and criteria for assigning prisoners to these facilities that do not necessarily identify the extraordinarily dangerous. There is a natural tendency, once super-maximum-security facilities are built, to fill them; standards for selecting prisoners for whom harsh conditions are warranted get diluted in practice. There is also a tendency to keep difficult prisoners in super-maximum-security facilities longer than is required in the interests of security and longer than is wise for the prisoners’ well-being. In our judgment, conditions at the MCF and the SHU do nothing to encourage the prisoners’ ability to reintegrate successfully into the general prison population or society. To the contrary, lengthy confinement at these facilities threatens prisoners’ physical and mental health and may well enhance the likelihood of repeated criminal or disruptive behavior.

By choosing to subject hundreds of prisoners to prolonged periods in extremely harsh and potentially harmful conditions that cannot be justified as reasonably necessary to ensure security or to serve the legitimate goals of punishment, the Indiana DOC has violated the prohibition on cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment contained in the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights and the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

The confinement of persons who are mentally ill in these facilities is particularly reprehensible. In Indiana, as throughout the United States, increasing numbers of mentally ill people are ending up in prisons that are not equipped to meet their mental health needs. Mentally ill people often have difficulty complying with rules, especially in prison settings where the rules are very restrictive and the stresses are intense. Many are aggressive or disruptive and, as a result, accumulate disciplinary records that land them in segregated confinement in super-maximum-security facilities. While 5 percent of the general prison population have a serious mental illness, over half of the inmates at the SHU are mentally ill. For some mentally ill inmates, placement in super-maximum-security conditions is a horror: the social isolation and restricted activities aggravate their illness and immeasurably increase their pain and suffering. In a tragic vicious cycle, their worsened mental condition leads to more rule infractions, such as self-mutilation, for which they receive the additional punishment of even more time in segregation. Compounding the tragedy of confinement in these conditions, Indiana’s super-maximum-security facilities are not equipped to provide appropriate mental health treatment for the mentally ill confined within them.

Warehousing severely ill and psychotic individuals under conditions that increase their suffering by exacerbating their symptoms, and in facilities that lack adequate mental health services, can only be characterized as cruel. In some cases, the suffering that results is so great that the treatment must be condemned as torture under international human rights law. We do not believe the Indiana DOC has the specific intent of tormenting mentally ill prisoners. But it places them in the MCF and the SHU because it has failed to create secure psychiatric facilities in which they can be safely confined and treated. That failure must be remedied.

As this report was being prepared for publication, we received word of a particularly egregious situation at the SHU that exemplifies the dangers of placing mentally ill prisoners in such facilities. Edgar Hughes is a thirty-five-year-old confined at the SHU who had been repeatedly hospitalized for psychiatric problems since his youth. When we interviewed Hughes in July 1997, the psychiatrists on our team concluded that he was actively psychotic, very depressed, and extremely paranoid. He felt persecuted by the guards and apparently had a history of “bombing” them with excrement. He reported to his family that he had had physical altercations with guards. In the early morning of September 11, 1997, he suffered a mysterious head trauma that caused severe brain damage. The current prognosis is that he will remain in a vegetative state. An official inquiry into the tragedy has been launched [20]. Based on the currently available facts, it appears Hughes was the victim of one of two situations: either he suffered severe physical abuse at the hands of correctional officers, or he underwent a severe psychiatric breakdown in which he injured himself. Either way, his confinement at the SHU caused a terrible and seemingly irreversible tragedy. We call on the State of Indiana to ensure that the inquiry into this incident is thorough and that anyone responsible is held accountable.

Recommendations

Pressed by inmate litigation and persistent scrutiny from local, national, and international groups concerned about the treatment of prisoners at the MCF and the SHU, the Indiana DOC has acknowledged that the egregiously harsh conditions at the MCF and the SHU are not necessary for all inmates there and that conditions can be ameliorated without jeopardizing the goals of security and discipline. By changing the facility’s management, the Indiana DOC secured a dramatic reduction in the use of excessive force at the MCF. It has initiated group recreation at the MCF and at the end of September, 1997 stated its intention to permit prisoners at the SHU with good behavior records to share out-of-cell recreation time in groups of two or three. It has committed to reviewing the length of confinement in supermax conditions and the proportionality of punishment for disciplinary infractions, and has agreed that many mentally ill prisoners do not belong in supermax units and that it needs to develop facilities geared to their psychiatric needs.

Human Rights Watch welcomes these limited steps and announced intentions. We hope that the Indiana legislature, the executive branch, and the public will support efforts by the Indiana DOC to improve conditions in the MCF and SHU. Some of the needed changes will not entail additional expenditures of any significance; others will be costly. We urge the State of Indiana to provide the financial resources necessary to bring its super-maximum-security facilities into line with international human rights standards. Based on three years of observing conditions at these facilities, we offer the following recommendations:

1. Offer Treatment and Conditions of Confinement Appropriate for Mentally Ill Prisoners

The Indiana legislature should:

- Enact legislation that bars the administrative or disciplinary segregation in conditions of extreme social isolation and reduced environmental stimulus of seriously mentally ill inmates or of inmates who are at significant risk of suffering a serious injury to their mental health if confined in such conditions.

- Provide the Indiana DOC and/or the Department of Mental Health with the necessary financial resources to properly house and treat inmates who should not be confined at the MCF or SHU because of their mental health condition or histories.

The Indiana Department of Correction should:

- Develop, or collaborate with the Department of Mental Health to develop, secure facilities to house and treat mentally ill inmates who cannot be confined in the general prison population because of the safety and security risks they pose, but who do not meet the existing criteria for in-patient hospitalization. These facilities should provide physical conditions and social interaction conducive to mental health and rehabilitation, and should be staffed by qualified mental health professionals.

- Undertake a comprehensive mental health evaluation of all inmates currently confined at the MCF and the SHU to identify those who should be excluded from segregated confinement because they are currently suffering from a serious mental disorder, have a history of severe mental illness or whose mental condition (e.g., brain damage, mental retardation, chronic depression) makes them vulnerable to deterioration if they remain in those facilities.

- Develop procedures to ensure that no prisoner sent to the MCF or to the SHU remains there for more than a brief period if they are persons for whom the risk is high that confinement in such facilities will cause serious mental health injury.

- Provide frequent monitoring by qualified health professionals of inmates at the SHU and MCF to identify those who need mental health services.

- Expand the range of mental health services available to inmates at the SHU and MCF, and grant inmates prompt access to such services.

- Provide sufficient staff to meet prisoners’ mental health needs. It should also provide adequate custodial staff to enable prisoners to be escorted as needed to meetings in private with mental health staff, medical visits, meetings with visitors, and other activities conducive to their mental well-being and rehabilitation.

2. Reduce Periods of Solitary Confinement

The Indiana Department of Correction should:

- Discontinue the policy of indefinite administrative segregation. Inmates should be assigned to administrative segregation for a fixed term that is not excessively long. Inmates should be able to reduce their time in administrative segregation through good behavior. No inmate should be assigned to an additional period of administrative segregation within three months of a prior period of segregation. Exceptions to this rule should only be permitted upon a finding, following a hearing, that the inmate constitutes a serious danger to prison safety and security and cannot be safely confined in a less restrictive setting. Such an inmate should also receive a mental health evaluation by an independent psychiatrist who must certify that the inmate is not suffering from severe mental disorders that would be exacerbated by continued segregation.

- Refrain from sentencing prisoners to disciplinary segregation at the MCF or the SHU for more than short periods of time unless they are guilty of extremely dangerous or violent actions, such as assaults against staff or prisoners causing bodily injury. Inmates should be able to reduce the period of disciplinary segregation through good behavior.

- Review disciplinary policies with the goal of instituting greater proportionality between sanctions for rules infractions and the type of infraction and, in particular, to reduce the amount of disciplinary time awarded for nonviolent infractions.

- Reduce the use of additional time in segregation as a punishment for violation of rules by segregated inmates. Explore alternatives that would serve the goal of promoting rule-abiding behavior by inmates without prolonging their time in segregation (e.g., use of increased privileges contingent on good behavior, training in anger and impulse control, and increased mental health services).

- Establish equivalent policies governing transfer to, release from, and privileges for disciplinary segregation inmates at the MCF and at the SHU.

3. Improve Physical Conditions

The Indiana legislature should:

- Provide sufficient resources to the Indiana DOC to finance the modification of the physical plant at MCF and the SHU to eliminate egregiously harsh and harmful conditions.

The Indiana Department of Correction should:

- Renovate the MCF and the SHU to create genuine outdoor recreation areas in which inmates are exposed to sunlight and can see outside of the facility, and indoor or outdoor recreation areas large enough to allow inmates to run at a reasonably high speed and to exercise with another person comfortably.

- Construct sufficient windows in cells at the SHU so that no prisoner is confined in a windowless cell for more than a very brief period.

- Replace the solid steel cell doors in use at the MCF with doors, such as those in use at the SHU, that allow prisoners greater opportunities for social interaction.

4. Eliminate Unnecessarily Harsh and Counterproductive Practices

The Indiana Department of Correction should:

- Establish a program of increased privileges, including enhanced access to congregate activities and educational and vocational activities, to reward and encourage infraction-free and responsible behavior by inmates confined in administrative and disciplinary segregation.

- Encourage increased contact between inmates and their families and communities. The department should end the routine shackling of all inmates during visits and permit selected inmates to have contact visits with their families. It should also increase access of inmates at the SHU to telephones.

- Discontinue its practice of releasing inmates into society directly from segregated confinement. Prior to release from the MCF or SHU, all inmates should be provided effective transition programming to facilitate social readjustment.

- Reduce racial tensions in the MCF and the SHU by, among other things, undertaking aggressive efforts to recruit and train African-Americans as correctional staff, providing increased racial sensitivity training to staff, and emphasizing to staff through the use of internal disciplinary mechanisms that racial harassment and discrimination will not be tolerated.

- Enhance monitoring and supervision of correctional staff and utilize disciplinary mechanisms to prevent and punish the inappropriate, unnecessary, or excessive use of physical force.

The Indiana legislature should:

- Instruct the Indiana DOC to review conditions and practices at the MCF and the SHU to identify measures needed to better promote the rehabilitation of inmates and their ability to lead law-abiding lives upon release. The review should be undertaken with the participation of outside professionals with correctional, mental health and other relevant experience and with input from inmates and should result in a public report that includes findings and suggested reforms.

5. Monitor Conditions at the MCF and the SHU

The Indiana legislature should:

- Create a permanent independent ombudsman with the authority and adequate staff to monitor conditions in the MCF and the SHU; report its findings to the Indiana DOC, the legislature, and the public; and make recommendations for reform. * Create a permanent independent review committee composed of qualified mental health professionals who are not employed by the Indiana DOC to monitor mental health care in the Indiana prison system.

III. The development of super-maximum-security confinement in Indiana

The National Trend Toward Super-Maximum-security Prisons

The prototype for modern super-maximum-security incarceration is the federal penitentiary at Marion, Illinois [21]. In the 1970s, federal prison authorities began directing the most dangerous federal prisoners to Marion, which was charged with providing “long-term segregation within a highly controlling setting” for these inmates [22]. In October 1983, after years of mounting tensions, Marion experienced a week of violence during which two guards were knifed to death, one inmate was murdered, and others were attacked. As an emergency response to the crisis, Marion was “locked down”-leaving prisoners confined to their cells twenty-three hours a day-initiating a large-scale experiment in solitary confinement [23].

The Marion regime dramatically reduced the level of violence and disruptive conduct at the facility [24], prompting other prison authorities to try to replicate it. Thirty-six states and the federal government currently operate a total of at least fifty-seven super-maximum-security units, called “supermaxes,” built either as annexes within existing prisons or as free-standing facilities. Construction under way will increase nationwide supermax capacity by nearly 25 percent. Although conditions and policies vary somewhat from facility to facility, they all utilize the basic model initiated at Marion: dangerous or disruptive prisoners are removed from the general population and housed in conditions of extreme social isolation, limited environmental stimulation, reduced privileges and services, scant recreational, vocational or educational opportunities, and extraordinary control over their every movement.

Inmates in super-maximum-security facilities are usually held in single cell lock-down, what is commonly referred to as solitary confinement [25]. The more

precise corrections terminology today for such confinement is segregation, which includes administrative segregation, protective custody, and disciplinary detention [26]. Inmates in super-maximum-security segregation are not denied all human contact, but congregate activities with other prisoners are usually prohibited; other prisoners cannot even be seen from an inmate’s cell; communication with other prisoners is prohibited or difficult (consisting, for example, of shouting from cell to cell); visiting and telephone privileges are limited. The new generation of super-maximum-security facilities also rely on state-of-the-art technology for monitoring and controlling prisoner conduct and movement, utilizing, for example, video monitors and remote-controlled electronic doors. “These prisons represent the application of sophisticated, modern technology dedicated entirely to the task of social control, and they isolate, regulate, and surveil more effectively than anything that has preceded them” [27].

The rationale behind supermax facilities and units is rather simple: in an era of rampant violence in many prisons, the segregation of dangerous inmates allows inmates in other facilities to serve their time with less fear of assault [28]. the extreme limitations on inmates’ freedom in such facilities protects both staff and inmates; and the harshness of supermax conditions is believed to deter other prisoners from committing acts that might result in their transfer there.

Super-Maximum-security Confinement in Indiana

Indiana opened its first super-maximum-security unit, then called the Maximum Control Complex (MCC), in April 1991. Although only a handful of prisoners were held at the facility during its first few months of operation, reports of harsh conditions, frequent beatings, and other abuses quickly began to circulate. By late September 1991, thirty-five prisoners were housed there, nearly half of whom had launched a month-long hunger strike to protest conditions [29]. Senator Anita Bowser, an Indiana state senator interested in prison issues, exercised her right as a state legislator to view the MCC during this period; shocked by conditions there, she publicly condemned the facility as “dehumanizing” [30]. The hunger strike-the first of several-ended when prison authorities obtained a court order to force-feed the protesters. A few months later, in an even more dramatic attempt to attract outside scrutiny of the facility’s conditions, an MCC prisoner severed his fingertip and sent it to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

In May 1992 the Indiana Civil Liberties Union, a local ACLU affiliate, filed suit challenging conditions at the MCC, as well as the criteria for inmates’transfer there [31]. The complaint in this federal class action charged numerous constitutional violations, including the arbitrary and excessive use of force by guards, the frequent use of physical restraints as punishment, and the misuse of chemical agents. Another hunger strike began at the MCC that month, with some inmates again lasting more than a month without food [32]

In December 1993, a second super-maximum-security facility opened in Indiana. Called the Secured Housing Unit (SHU), it was built as an annex of the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility in Carlisle, a $124 million “state of the art” prison facility that had opened the previous year. Again, reports of abuses were frequent, and inmates conducted long hunger strikes to protest conditions.

In February 1994, after months of negotiation, the class action suit was settled, with the parties accepting a comprehensive Agreed Entry that addressed many of the plaintiffs’ complaints. A number of MCC prisoners rejected the Agreed Entry, however, because it did not end administrative segregation nor shut down the MCC. While the settlement would improve conditions, it left intact the fundamental premise and design of prolonged solitary confinement and social isolation as a management prerogative. Seven months later, the plaintiffs returned to court, claiming that MCC authorities were erecting obstacles to frustrate the terms of the Agreed Entry; the court agreed with regard to several of their contentions (regarding access to law library, legal materials and law clerks) but rejected others [33].

In June 1996, the name of the MCC was changed to Maximum Control Facility (MCF). In October 1996, the Indiana DOC obtained a modification of the Agreed Entry to permit it to turn three-quarters of the MCF into a facility housinginmates serving long-term disciplinary sentences from around the state [34]. Because the Indiana DOC had to secure plaintiffs’ consent to the modification of the Agreed Entry, it agreed to provisions governing the treatment of and conditions for disciplinary segregation inmates at the MCF that differed in certain regards from those in place at the SHU. For example, the modified Agreed Entry requires two hours of recreation per day for disciplinary segregation inmates at the MCF, compared to the half hour per day then provided at the SHU.

The history of litigation over super-maximum-security conditions in Indiana is not limited to the class action lawsuit. Individual prisoners at the MCF and the SHU have brought dozens of lawsuits alleging unconstitutional conditions or practices. Although such suits are normally brought pro se-by prisoners acting as their own legal counsel-some of them have been successful. In 1995, for example, an MCC prisoner who was placed in four-point restraints for a total of fifteen days won summary judgment in his case against the MCC’s superintendent.

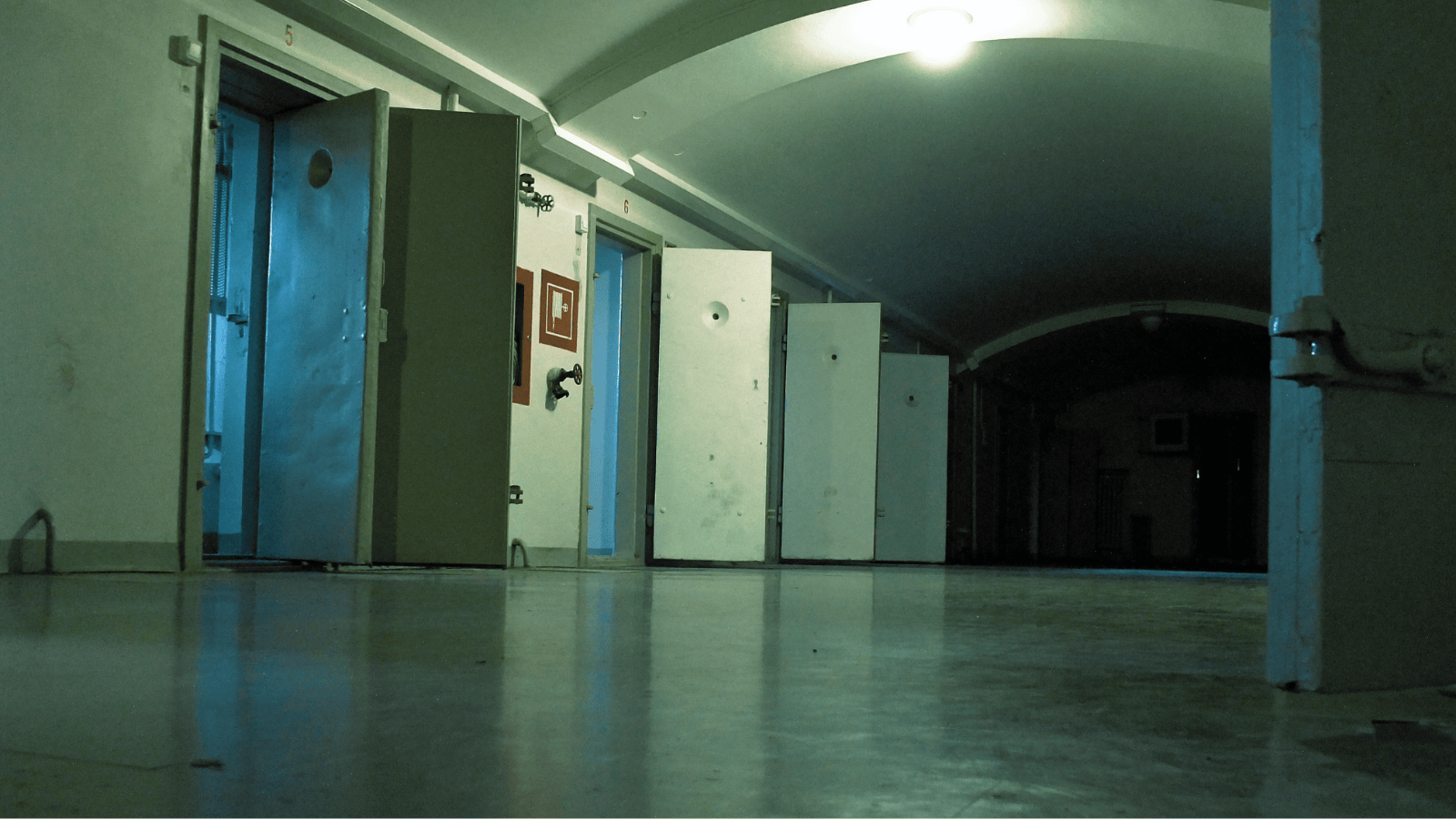

IV. The physical environment

Both the MCF and the SHU are new facilities, built within the last decade. With respect to their design, construction, and choice of building materials, the architectural truism that “form follows function” seems particularly apt. Even though they provide a temporary living space-or, in many instances, a not-so-temporary living space-for the hundreds of prisoners confined in them, the facilities offer few concessions to this aspect of their use. Instead, their fundamental and overriding concern is security, and even their most minor details are shaped with this function in mind.

Within the custodial portions of the two facilities, there is little to relieve the visual monotony of concrete and steel. “[D]esigned to reduce visual stimulation,” their interiors are characterized by “a dull sameness in design and color” [35]. The MCF has color-coded sections distinguished by different shades of pastel paint, and the SHU has green cell doors and pea-green detailing, but otherwise the two facilities lack decoration. In overall impact, they are cold, hard, and austere.

Layout

In their physical layouts, the facilities are designed to isolate prisoners into small, manageable sub-populations. Each one is divided into four cell blocks, called “pods,” which contain cells, showers, recreation areas, medical examination areas, etc., as well as a central control booth for corrections staff. Since each pod is essentially a self-contained unit holding the same stock of equipment as any other pod, inmates rarely need to leave their pods, facilitating security and control by reducing inmate movement around the facility.

The MCF’s four identical pods are designated as A-, B-, C-, and D-pod. Reminiscent of Jeremy Bentham’s famous panopticon, each pod centers around a raised control room with glass walls. Ranged around the control room are four two-story housing sections; each of which has fourteen cells (including one cell reserved for use as a “satellite” law library) and two showers. Each pod also holds five indoor and two outdoor exercise areas, a medical examining room, and two small counseling rooms. The correctional officers stationed in the control rooms can see the corridors of each housing section, the front of each cell, and the interior of all recreation areas (through the areas’ clear walls). They can also operate the pod’s electronically controlled gates but not the cell doors, whose separate controls are adjacent to them.

When Human Rights Watch first inspected the MCF, in June 1995, the facility held only Level 5 administrative segregation prisoners [36]. A-pod held prisoners who had accrued at least twelve consecutive “vested months,” that is, twelve months without any serious disciplinary infractions; D-pod held prisoners in medical quarantine and on disciplinary status (in two separate housing sections); C-pod held the remainder of the MCF population, and B-pod was not in use. When we returned in July 1997, the facility had filled up substantially due to the arrival of Level 4 disciplinary segregation prisoners. At that time, only the A-pod held Level 5 prisoners; the other three pods held Level 4.

The SHU’s four identical pods are somewhat larger than those of the MCF and are differently designed. Upon entry to the SHU one reaches a centralcorridor; in one direction lies the “A-side” of the SHU, with pods A-East and A-West located across from each other, and in the other direction lies the “B-side,” with pods B-East and B-West. B-West differs from the other three pods in that it holds only WVCF inmates sentenced to short-term disciplinary segregation; the other pods hold inmates from prisons all over the state who have been sent to the SHU for long-term segregation. Although no pod within the SHU is formally classified as an “honor” pod or as a disciplinary pod, long-term inmates enter the SHU in B-East, which is considered the “difficult” pod. If they maintain a record of good conduct they may be transferred to the A-side, where it is considerably quieter and where a substantial number of inmates have televisions.

As in the MCF, each pod at the SHU centers around a raised control room. Radiating out from the control room are six separate two-story housing sections arranged in parallel pairs. Each housing section contains twelve cells-six in the upper tier and six in the lower tier-two showers, and, at the opposite end from the control room, an outdoor recreation area. A skylight covers each pair of housing sections, allowing a limited amount of natural light to filter down into the prisoners’ living quarters.

Through the glass walls of the control room, correctional officers can see down the corridors of the housing sections, but not into the individual cells. They can also operate the electronically controlled doors of the cells and walkways, and can hear inmates through an intercom system. Although the officers cannot see into the exercise areas, which have solid walls, they can watch exercising inmates using video monitors. Besides the housing sections and the control room, each pod contains a counselor’s office, a medical examining area, a dental area, a satellite law library, and a hair-cutting room.

Cells

The most striking thing about the cells at the MCF is their imposing doors. Made of solid steel, interrupted only by a small, approximately eye-level clear window and a waist-level food slot, they effectively cut inmates off from the world outside the cell, muffling sound and severely restricting visual stimulus. “Boxcar” cell doors such as these have been reported at Marion and at other super-maximum-security prisons, although not all such facilities use them [37].

Each rectangular MCF cell measures twelve feet ten inches by five feet eleven inches and has a concrete ceiling, walls and floor. Its main furnishing is a narrow poured concrete bed, stretching away from the door down the long side of the cell, and a mattress. At one end of the bed, across from the door, is a rudimentary concrete desk; to use it, the inmate must sit on the bed, where he lacks back support. Above the desk is an extremely narrow window, like those used for cross-bows in medieval castles: impossible for a person to fit through. Next to the desk, and facing the bed, is a stainless steel combination toilet and sink. On the wall by the other end of the bed, next to the door, is a high shelf for a TV. Below this shelf, a two-by-three-foot section of wall is marked off: inmates are permitted to affix pictures and posters within this space. Otherwise, the walls of the cell must be kept bare.

MCF cells have fluorescent lighting and stark walls, painted ivory. At present, inmates may turn off one light and darken the cell somewhat, but a seven-watt fluorescent bulb stays on twenty-four hours a day. Prior to an agreement reached in 1994 after litigation, this “night light” was twice as bright.

In contrast to the solid cell doors at the MCF, the cell doors at the SHU are made of a perforated metal screen. Although it is somewhat disorienting to look at people through the heavy screen, approximately 60 percent of an image can be seen through it. The main benefit of the screen, as compared to the steel doors at the MCF, is that it allows sound to travel more easily, so that prisoners can converse with a larger number of other prisoners [38].

Numerous cells in the B-East pod of the SHU have a special protective covering. Called “lexan,” it is a clear plastic shield that covers the entire front of the cell. These cells are colloquially referred to as “bubbles” and are used for inmates who have a history of throwing bodily fluids-i.e., urine or feces-or spitting [39]. The lexan shield makes it impossible for inmates to throw anything outside the cell; it also muffles sound. Lexan-covered cells become very stuffy inside, and are even more uncomfortable than other cells in the summer heat. According to one prisoner’s description of living in such a cell: “It’s stuffy in here. Your head can’t get air. You don’t breath. You can’t think clearly.”

SHU cells, which are approximately eighty square feet in size (seven by twelve feet), are shaped like a rectangle with one corner shaved off. They have no windows, leaving prisoners without any glimpse of the outside world. Each cell contains a concrete bed with a plastic-covered mattress, a shelf by the bed, a fixed table and stool with no back support, and a stainless steel combination sink and toilet. Inmates are not supposed to attach anything to the cell walls, although we noticed a great degree of leniency in the application of this rule [40]. The cell’s forty-watt fluorescent light is located over the toilet. Between 9:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. the prisoner controls it; the rest of the time it is controlled by corrections staff, and is normally kept on. Even when the main light is turned off, however, a seven-watt “night light” remains lit [41].

Prisoners in both the MCF and SHU are allowed to keep a limited amount of personal property in their cells. Both facilities have written rules that set out precisely how many books, magazines, pens, etc., a prisoner is allowed to retain, as well as what kind of items are permissible. (Some of these rules are quite strict. Until recently, for example, prisoners at the SHU were only allowed to keep the flexible inner cartridge of ballpoint pens; their hard plastic shell was confiscated for security reasons.) Each cell has a property box in which to store such materials.

Recreation Areas

The MCF has both indoor and outdoor recreation areas, while the SHU has only outdoor areas. The differences between “indoor” and “outdoor” areas, however, are not as great as their names suggest. Because of their small size, meager array of equipment, concrete floors, high concrete walls, lack of outside view, and general sterility, both types of recreation areas provide little variation from confinement in a cell. Indeed, a number of prisoners at both facilities aptly described them as “oversized cells” or “dog runs.” Outdoor recreation areas merit their name only to the extent that being outdoors is defined by a narrow view of the sky and a breath of fresh air. Standing in the outdoor area is akin to being at the bottom of a well.

The MCF’s indoor exercise areas are irregularly shaped clear boxes of roughly 150 square feet containing a rudimentary stationary bicycle (quite unlike the exercise bicycles found at health clubs) and a telephone. The outdoor recreation areas, which measure twenty-seven feet two inches by nine feet five inches, are roughly pie-slice-shaped and contain a pull-up bar, a sixteen-foot-high basketball hoop, and a basketball. Approximately a third of their walls are constructed of clear plastic facing the interior of the prison which allows the guards in the control room to watch inmates exercise; the rest of their walls are of solid concrete. Since these walls are over two stories high, inmates have no view outside of the facility.

At the SHU, each range has an adjoining outdoor recreation area of approximately fifteen by twenty-four feet, with over two-story-high concrete walls and a concrete floor. High above, half of the area is covered with a clear plastic and half with a mesh screen. Except for those outdoors at the right moments in the summer, most prisoners are rarely touched by the sun. In the winter, besides being freezing cold, the outdoor areas can get icy, and in icy weather the inmates’ exercise period is canceled (to prevent injuries) [42]. Because of such conditions, there can be long periods of time when the inmates have no possibility of out-of-cell exercise.

Like the MCF, the SHU has rudimentary exercise bicycles in its exercise areas, although these were installed only after the facility had been in operation for a few years. Besides these bikes, each exercise area has a sixteen-foot-high basketball hoop and a basketball.

Air, Light, and Climate

Except for their outdoor recreation areas, the MCF and the SHU are sealed environments. Inside the two facilities, there is little natural light and no fresh air, in violation of the U.N. Standard Minimum Rules [43]. Sometime in 1994, under the orders of former Superintendent Charles Wright, twenty-eight cell windows in the MCF were painted over because staff had complained of inmates’ watching or harassing them from the windows. Because the paint exacerbated the facility’s dearth of natural light, it was removed in April 1995 with the arrival of a new superintendent.

An important environmental difference between the two facilities is that the SHU relies on fans for cooling while the MCF has air-conditioning. Prisoners stated that in the era of Superintendent Wright the air-conditioning was sometimes set extremely low (i.e., down to 40º Fahrenheit) as a punitive measure, leaving prisoners shivering in their cells. The 1994 Agreed Entry specified that cell temperatures should remain between 68º and 75º Fahrenheit, a rule that prisoners confirmed was followed.

Temperatures in the SHU, in contrast, may reach 100º Fahrenheit in the summer; cell interiors, particularly in lexan-covered cells, are stifling. SHU administrators have stated that they plan to install air-conditioning; to our knowledge, however, this has not been done.

V. The inmate population

Prisoners are not sent to the MCF or the SHU because of their original crimes. No judge ever sentences a defendant to serve time in either facility, and no one ever begins his prison sentence in one. Rather, prisoners are transferred to these units by the Indiana DOC because of the department’s negative assessment of their conduct while in the prison system.

According to the DOC commissioner, MCF and SHU prisoners are “the most disruptive, violent, and unmanageable persons housed with the Department” [44]. It is these inmates’ extreme behavior that, in the DOC’s view, justifies the facilities’ correspondingly extreme security and control measures. Human Rights Watch, however, is unconvinced that the criteria and procedures employed in selecting prisoners for placement in these facilities actually separate out those prisoners in need of such extraordinary control measures. We are concerned, in particular, that the MCF and SHU house some prisoners who would more appropriately be confined in less restrictive settings. Moreover, although we were unable to ascertain the proportions of violent or dangerous prisoners, we did discover shocking numbers of severely mentally ill prisoners who are held in these facilities [45].

Heightened scrutiny and safeguards should be utilized before a state subjects any prisoner to the harsh conditions of prolonged confinement in segregated housing. In addition, the placement of individuals in super-maximum-security settings should be continually reviewed to ensure that no person is confined in such conditions longer than is necessary [46]. Inmates who are mentally ill or are particularly vulnerable to the mental health risks of segregated confinement should not be housed in such conditions at all. These basic principles are not observed in Indiana.

Criteria and Procedures for Assignment

Administrative Segregation at the MCF

The MCF was established as an administrative segregation facility. It is Indiana’s only Level 5 institution, the state’s highest security classification. Assignment to MCF Level 5 is not deemed punishment, nor is it imposed upon conviction of rules infractions through a formal disciplinary proceeding. Consistent with the position that assignment to the MCF Level 5 is a management classification decision and not a disciplinary one, the Indiana DOC does not provide prisoners with an opportunity for a formal hearing regarding their proposed assignment to the facility [47].

The class action lawsuit alleged that criteria for assignment to the MCF (then MCC) were excessively vague and discretionary and that DOC used transfer to the MCF as a method of retaliating against or punishing disfavored prisoners, e.g., politically active or litigious prisoners. The lawsuit also alleged that minor incidents such as throwing water on a guard could result in transfer to the MCF.

The negotiated settlement to the class action established substantive criteria for transfer to the MCF, greatly constraining the DOC’s discretion. Under the terms of the Agreed Entry, the DOC can assign a prisoner to MCF Level 5 only if that person is not mentally ill and has a confinement history including at least one of the following factors: escapes with attempts to cause physical harm or serious property destruction; assaultive behavior against staff or prisoners causing serious bodily injury or death; rioting or inciting to riot; intensive involvement in violent gang activities; or aggressive sexual conduct or rape [48]. Although an inmate may contest his assignment, either in person to his classification supervisor, or in writing, and may appeal in writing a decision to transfer him to the MCF, he is provided no meaningful opportunity to present reasons and evidence supporting his claim the assignment is inappropriate.

Prisoners are assigned to the MCF Level 5 for an indefinite period of time. A prisoner’s classification and assignment to the MCF Level 5 is supposed to be reviewed after twelve months; as part of that review, the Indiana DOC is to interview the prisoner and discuss with him information pertinent to the decision of whether or not to maintain him at the MCF. Inmates insist that the review is proforma and, in their view, not a genuine effort to ascertain whether their continued confinement in Level 5 is necessary.

The total time a prisoner remains at the MCF depends primarily on the accumulation of “vested months”: months in which the prisoner remains free of serious rules violations. Prisoners who have twenty-four consecutive vested months, or a total of thirty-six vested months (with the last six months consecutively), must be transferred out of the MCF. Prisoners may be awarded additional vested months for “exceptionally good behavior” and may lose accumulated vested months upon conviction of rules infractions.

Some prisoners never accumulate sufficient vested months to permit them to transfer out of the MCF. In the summer of 1997, for example, at least three prisoners had been there since the first year the facility opened.

Disciplinary Segregation at the MCF

Although construction of the MCF was considered necessary to house a growing population of dangerous offenders, when objective criteria for dangerousness were applied following the Agreed Entry, the facility remained largely vacant. Faced with this unoccupied space, the Indiana DOC obtained a modification of the Agreed Entry allowing it to use three pods of the MCC, or 165 beds, as a Level 4 disciplinary segregation unit (DSU), housing inmates serving long terms of disciplinary segregation.

Under the terms of the modified Agreed Entry, any adult male prisoners who has been sentenced after conviction of infraction(s) at a disciplinary hearing by the Conduct Adjustment Board/Hearing Officer, and sanctioned to a minimum of six months of disciplinary segregation, can be sent to the MCF-DSU to serve his disciplinary time, with the exception of those who are mentally ill and actively psychotic. Prisoners cannot be confined at the MCF-DSU for longer than two years, unless they have been convicted of class A or B disciplinary offenses during that period. Inmates with an unsatisfactory disciplinary record can remain confined at the MCF-DSU for years.

Disciplinary Segregation at the SHU

The SHU is solely a disciplinary segregation unit. Under Indiana DOC policy, prisoners who have accumulated at least two years of disciplinary segregation time for rules infractions are eligible for transfer there [49]. The disciplinary time is imposed by conduct adjustment boards or by a hearing officer following a formal hearing with certain due process safeguards [50].

The Indiana DOC does not have a published policy establishing a minimal threshold of violent or dangerous behavior for assignment to the SHU. Unruly or troublesome offenders can easily accumulate the requisite two years’ segregation time without ever posing serious threats to prison safety or security. There is no requirement, for example, of a history of hostage taking, organizing or causing a riot; assaulting others with an instrument capable of bodily harm, or attempted escape [51]. A SHU administrator told Human Rights Watch that other institutions often send their “management problems” to the SHU even though they have not engaged in serious assaults or dangerous behavior. By way of example, he cited a prisoner sent to the SHU because he continually masturbated in front of female staff at his home facility. Such conduct should obviously not be condoned; but it is difficult to see how it justifies treating him the same as someone who has attacked guards with a knife [52].

There is no limit on the amount of time a prisoner can be confined at the SHU. We interviewed prisoners at the SHU serving decades of accumulated disciplinary segregation time. No policies or court orders preclude the Indiana DOC from keeping them at the SHU for the entire period. In addition, whatever the original amount of segregation time to be served at the SHU, it can be extended because of infractions committed once there. Even if the infraction is relatively minor, or is the result of mental illness (as in certain cases of self-mutilating prisoners), it can result in additional segregation time.

Prisoners at the SHU and those being held in disciplinary segregation at the MCF are classified as Level 4 inmates. At the MCF, however, under the terms of the modified Agreed Entry, prisoners must be released from the DSU after two years there, barring conviction of any serious offense during that period. But prisoners can be confined indefinitely at the SHU, regardless of their conduct, until the end of the mandated disciplinary period.

In 1996, the DOC instituted a new policy permitting SHU inmates with twelve months of clear conduct history to apply or be recommended for early release. The decision whether to grant early release from the SHU is entirely discretionary, and there are no published criteria. At least one prisoner interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed frustration at not having been given any useful explanation for why his request for early release had been denied. We do not have figures on how many prisoners have benefited from the new policy.

Confinement of Mentally Ill Prisoners

A substantial proportion of the prison population in the United States is composed of people with serious mental disorders [53]. Their illness makes it difficult, if not impossible, for them to comply with prison rules and to adjust to the unique strictures of prison life. Within the population of mentally ill, a certain proportion exhibit their illness through aggression, disruptive behavior and violence. The mentally ill are also exceptionally vulnerable to abuse by otherprisoners, including sexual abuse [54]. For these and other reasons, mentally ill prisoners often accumulate long records of rules infractions and can pose very real security and safety challenges. The response of many prison administrators, including those in Indiana, is to confine them in super-maximum-security prisons in which symptoms of their illness are treated as disciplinary infractions and mental health services are inadequate [55].

Both the SHU and the MCF house prisoners who are seriously mentally ill. The problem is particularly severe at the SHU, where even the staff acknowledges that somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of the inmates are mentally ill [56]. These illnesses are not manifested in subtle symptoms apparent only to the discerning professional: prisoners rub feces on themselves, stick pencils in their penises, stuff their eyelids with toilet paper, bite chunks of flesh from their bodies, slash themselves, hallucinate, rant and rave or stare fixedly at the walls. The situation has been so intolerable that prisoners themselves have sought to bring to public attention the fact of the confinement of mentally ill prisoners at the MCF and the SHU and the impact of that confinement on those prisoners, as well as onthe rest of the prison population [57]. Keeping the mentally ill out of the MCF was a major goal of the class action law suit, and prisoners at the SHU have released public statements and prepared lawsuits denouncing the fate of the mentally ill confined there. In a statement released to the public, one SHU inmate asserted that another inmate:

“has been beaten repeatedly by the guards here. The man obviously has some psychological problems because he defecates and rubs the feces all over his body. The guards think it is funny and continue to harass him daily” [58].

The Agreed Entry settling the class action lawsuit prohibits the administrative segregation of mentally ill inmates at the MCF. The Modified Agreed Entry also prohibits the incarceration at the MCF-DSU of inmates who are mentally ill and actively psychotic, but it permits the incarceration there of mentally ill inmates whose conditions are being controlled by psychotropic medication. The Indiana DOC has not fully complied with these restrictions. There are no regulations prohibiting or limiting the confinement of mentally ill prisoners at the SHU.

Among the two dozen MCF inmates interviewed in July 1997 by the psychiatrists on our team, at least five were mentally ill and not receiving medication or treatment. The following are the psychiatrists’ evaluations of two of these inmates [59]:

Prisoner Jones had two psychiatric hospitalizations as a teenager [60]. He has a history of hallucinations and continues to hear voices occasionally at the MCF as well as presenting emotional flattening and paranoia-all signs of schizophrenia.

Prisoner Smith is suffering from a paranoid delusional disorder.While in general population at his home institution, he had been treated with an anti-psychotic medication, but he is not being given any treatment at MCF. This inmate frequently verbally and physically assaults MCF guards; his behavior is clearly influenced heavily by his delusions, yet the only “treatment” he receives is additional punishment.

Mentally ill prisoners interviewed at the SHU include:

- Prisoner Davis has had severe psychiatric difficulties since the age of six; prior to his incarceration he had been in a state mental hospital for five years. He is a severe self-mutilator who is compelled to cut himself by voices that tell him to do it.

- Prisoner Johnson is actively psychotic. He hears voices and suffers from paranoid delusions that cause him to act out against guards. He was on a variety of psychiatric medications before coming to the SHU, but has refused them since coming there. His disciplinary infractions at the SHU appear to be directly related to his psychosis.

- Prisoner Washington is psychotic. He is a severe self-mutilator with a history of brain damage and seizures. He self-mutilates in response to voices telling him to kill himself.

- Prisoner Thomas is delusional and thought disordered; his speech is disorganized and tangential, with loose associations. He believes that he is “attached to an alien affiliation” and that he has been forced to commit treason against the United States. He also claims that he is a woman, but “they haven’t found his vagina yet.” He said that he shot his mother when he was three years old, but does not know if she died or not. He alsoreported that he believes that there is a radio in his nerves that is broadcasting. He often picks at his ear to see if the receiver is in there but can’t find it. He still believes it is there. He also gets messages through “federal codes” in his cell.

- Prisoner Brown has had seizures and psychiatric symptoms since childhood. He has bipolar disorder and a severe anxiety disorder, a phobia about being alone in a cell, and many features of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. After he has been in his cell for awhile, his anxiety level rises to an unbearable degree, turning into a severe panic attack replete with palpitations, sweating, difficulty breathing, and accompanying perceptual distortions and cognitive confusion. He mutilates himself-for example, by inserting paper clips completely into his abdomen-to relieve his anxiety and to be removed from his cell (for medical treatment).

- Prisoner Green is a severely ill individual who hears voices telling him that correctional officers are trying to kill him and that he should draw a circle on the floor with blood in it to make himself safe. He self-mutilates to relieve the pressure which builds up as a result of the voices. Most of his disciplinary reports have been for self-mutilating.

- Prisoner White is severely mentally ill and has been since childhood. He began psychiatric medication at age thirteen. He finds being alone intolerable: it makes his auditory hallucinations worse and makes him paranoid. This causes him to either mutilate himself or to assault correctional officers. This inmate also appears to be at best borderline mentally retarded.

- Prisoner Black has been on psychiatric medication since the age of ten years old for hearing voices and what he calls “psychological illusions.” He has had several previous psychiatric hospitalizations. He describes visual hallucinations of seeing ghosts, animals, people and things move. Auditory hallucinations are outside of his head, they are sometimes about Jesus, they take up to 500 different forms and talk to each other. They sometimes command him to kill himself although he has not made any previous suicide attempts. He is obviously severely mentally retarded and appeared to be blithely indifferent to his conditions. Because of his profound impairment, it is doubtful that he can fully understand the consequences of his behavior or “learn a lesson” from disciplinary segregation.

- Prisoner Hunt first saw a psychiatrist at age twelve because he had delusions that he was Jesus Christ. He remains psychotic, with delusions that he has been given a mission to kill people who do not believe in white supremacy [61].

- Prisoner Cooper is so severely mentally retarded that it was difficult to complete a psychiatric interview with him. His facial features are dysmorphic, and he appears to be microcephalic (these are related to a chromosomal or congenital condition which also causes his mental retardation), so that even without testing any physician would recognize that he is mentally retarded. In addition, his speech is dysarthric and severely impoverished. He cannot possibly understand fully the consequences of his actions and the rules that he is expected to follow in prison [62].

VI. A day in the life

Within the sterility and monotony of the physical environments of the MCF and the SHU, prisoners experience extraordinary social isolation, unremitting idleness, and few educational or vocational opportunities. With minor exceptions, a prisoner’s entire life is circumscribed within the four walls of his cell. Prisoners’ minimal physical requirements-food, shelter, clothing, warmth-are met, but nothing more [63]. Indeed, the Indiana DOC makes little claim that its penological goals at the MCF and the SHU extend beyond incapacitation and punishment. Neither facility offers a regime calculated to assist the inmate develop his ability to lead a peaceable life upon return to general population or upon release to society.

Many critics describe supermax conditions such as those at the MCF and SHU as sensory deprivation. It is more accurate to describe life in those facilities as one of extremely limited environmental stimulation, one in which perceptually informative inputs are limited [64].Their world is cramped, claustrophobic, and austere. Inmates can spend years of solitary lives, surrounded by the noise of others but without the opportunity to develop normal social relationships. If they live in the SHU they can spend years without seeing any part of the outside world except a bit of sky through the screen covering half of the top of the outdoor exercise area, indeed without seeing anything farther away than the end of the pod [65]. At the MCF, the benefit of the small window in each cell is outweighed for many prisoners by the solid steel door, which shuts each inmate into, as one called it, his “own little tomb.”

Social Isolation

One of the defining features of super-maximum-security confinement is its restrictions on prisoners’ social interactions [66]. Regardless of why they wereassigned to the MCF or the SHU, all inmates are confined alone in their cells twenty-two or twenty-three hours a day. While in their cells, they cannot see each other. They eat alone from food trays passed by guards through a narrow port in the cell door. Most exercise alone. There are no group classes, programs, or religious services. Even social interaction with guards is highly limited: guards avoid contact with prisoners except to serve them food through a feed slot in the door, handcuff and shackle them for time outside the cell, and, on occasion extract them forcibly from their cells (see discussion below).

Although ordinary social interaction-the varied experiences, gestures and exchanges of people living together in a community-is impossible, inmates nonetheless manage to communicate. They call out to immediate neighbors and pass notes using ingenious systems. Indeed, in their conversations with Human Rights Watch representatives, some inmates demonstrated considerable knowledge about the lives of other inmates.

In the MCC’s initial months, more drastic forms of social isolation were imposed: a few prisoners were placed alone in pods, or placed in pods with only one or two other prisoners. Paul Komyatti, the second prisoner to be transferred to the MCC after it opened, remained in A-pod all alone for three weeks in July 1991 [67]. At the SHU, similarly, two extremely mentally disturbed prisoners have been placed in a pod that is empty but for them; prison officials say they are kept away from other prisoners because other prisoners taunt them and encourage them to hurt themselves.

The atmosphere in the cell blocks is sometimes one of noisy anger, particularly at the SHU. To some extent, this reflects the presence of numerous mentally ill and disordered inmates with problems of impulse control and excessive anger. But the enforced lack of productive social contact also seems to stimulate considerable tension and animosity among prisoners. Prisoners yell and argue with each other. At the SHU, racial slurs abound [68]. Some prisoners expressed the view that the hostility and tensions build because prisoners know they harass their fellows and shout obscenities with impunity, given that the lack of physical contactbetween prisoners precludes retaliation. Prisoners also said that some prisoners even throw feces or urine into the cells of others when they are being escorted down the range, something that they would not do if they knew they would have to share space with each other, such as during group recreation. Prisoners at the SHU criticized the correctional staff for permitting the noise level at the SHU to reach excessive levels, interfering with the lives of others, and claimed that guards have at times deliberately permitted prisoners to throw human waste on others.